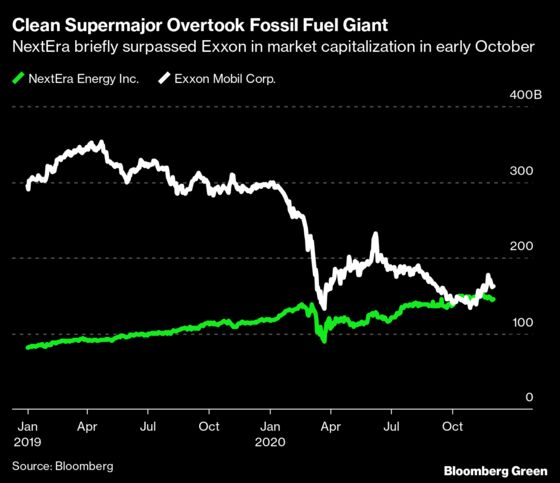

It spent millions to block homeowners from embracing solar panels, fought against hydropower, and pushed for an energy project next to a beloved national park. Its value competes with Exxon Mobil Corp.’s. Its longtime chief executive officer is a registered Republican.

Yet NextEra Energy Inc., the world’s biggest investor-owned generator of wind and solar power, has emerged as an unlikely green giant with a knack for throwing its considerable weight behind initiatives and policies that are pushing the U.S. into a future of zero-emissions electricity. Few companies appear better poised to benefit from the Joe Biden era.

NextEra isn’t a cheerleader for climate action like cleantech stalwarts Sunrun Inc. or Tesla Inc., and its CEO, James Robo, doesn’t tweet about saving the world. Founded as an ordinary Florida utility almost a century ago, the company backed into renewables by taking a stake in early wind farms whose developers owed it money. Since then it has shrewdly used dealmaking, scale, tax credits, and aggressive lobbying to grow into a powerhouse—all while keeping such a low profile that most people have never heard of it.

The market forces that drove down costs for renewable energy, backed by powerful incentives from state governments, have allowed NextEra to prosper even under President Trump. Despite tariffs on solar equipment from China and aggressive federal efforts to boost coal and gas, its profits rose from $2.9 billion in 2016 to $3.8 billion last year.

Biden plans to revive the fight against global warming abandoned by Trump with an ambitious $2 trillion proposal focused on creating a nationwide emissions-free electricity grid in just 15 years. That will require cooperation from Congress and an unprecedented private-sector build-out of renewable power plants and large-scale batteries. Its implementation would be good news for NextEra, which has wind and solar farms in two dozen states and four Canadian provinces, producing enough power to light up Greece. “These guys are the dominant player,” says Kit Konolige, senior utilities analyst with Bloomberg Intelligence. “They’re first on the list for anyone who wants to get renewables built.”

NextEra’s strategy relies heavily on taking advantage of state and federal incentives and shunning publicity. The company has made use of state-level requirements for utilities to buy more renewable power, targeting building projects in those states before wind and solar became cheap enough to be profitable nationwide. This approach also involves mining federal tax credits—$3.1 billion over the last 10 years, according to filings—to help finance growth. It’s in the enviable position of taking credits aimed at a struggling new industry and using the lobbying and political muscle of a huge power company to bake those credits in. The fossil fuel industry, meanwhile, gets billions of dollars a year in tax subsidies, including a special deduction for the costs of drilling new domestic wells.

NextEra spent $4.1 million last year lobbying federal lawmakers and the Trump administration, according to data compiled by the Center for Responsive Politics. “That’s pretty high,” says Dan Auble, a senior researcher with the nonprofit group, which tracks the influence of money in politics. NextEra has become the seventh-biggest lobbyist among 156 utilities. “Both lobbying and campaign contributions contributions are an investment in getting your issues in front of the people who need to see it.”

The company uses its lobbying muscle even when the results don’t promote renewable energy. In Florida, for example, NextEra subsidiary Florida Power & Light joined other utilities to spend $20 million promoting an unsuccessful 2016 ballot initiative that would have curbed rooftop solar arrays, drawing criticism from Al Gore. “Over the last several years, NextEra has been very aggressive against customer-owned solar,” says Alissa Schafer, a researcher with the Energy and Policy Institute, a clean energy advocacy group.

In Maine, the company tried to block a 145-mile hydropower transmission line sought by Avangrid Inc., challenging the project’s government approvals. In a complaint to federal regulators, the rival company said NextEra had “taken every opportunity, both in the open and behind the scenes, to oppose, delay, and derail” the project, including funding opposition groups, because it posed a threat to NextEra’s power plants in the region. “In doing so,” Avangrid wrote, “NextEra is purposely trying to thwart the goals of Maine and Massachusetts to obtain more renewable power.”

Even some of the company’s renewable efforts end up angering environmentalists. In California, it spent more than $768,000 in the most recent legislative session pushing an unsuccessful bill that would have benefited a large-scale energy storage project on the edge of Joshua Tree National Park.

NextEra spokesman David Reuter says that while it doesn’t comment on specific political contributions, all are funded by shareholders and employees rather than customers. The company makes all the proper disclosures and follows the applicable laws, he adds. “Since every aspect of our business is impacted by policy decisions at every level of government, it’s particularly important for us to be involved and be a leader,” Reuter says.

NextEra’s route to renewables was decidedly roundabout. It started life in 1925 as electric utility Florida Power & Light. A pair of deals, starting in the 1990s, radically altered its course. First, the company loaned money to some wind farm developers; when they later ran into financial trouble, NextEra forgave their debts in exchange for a majority stake in the farms. Then, in 2002, it renegotiated an agreement with General Electric Co., which had signed a contract to supply it with natural gas turbines for power plants. Robo, who’d come to NextEra from GE to serve as vice president for corporate development and strategy, saw that the market for gas plants was in a lull. So he persuaded his former colleagues to substitute wind turbines instead.

John Bartlett, president of Reaves Asset Management, compares the turbine swap to 3M’s fortuitous development of the Post-it Note—a simple idea that created an unanticipated windfall. “That’s one of the great strokes of industrial genius,” Bartlett says. Reaves owns about $170 million in NextEra shares.

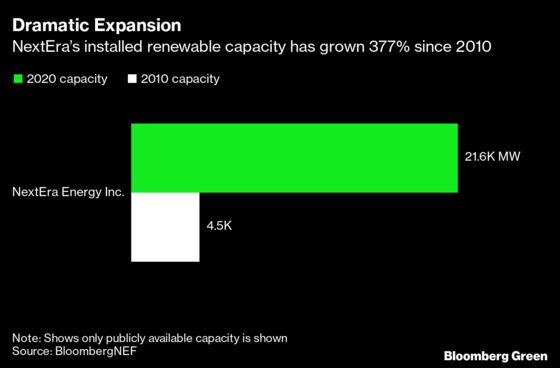

NextEra’s head start and scale worked in its favor throughout the 2000s, as states started requiring local utilities to use more renewable power. “We had advantages across the board,” Lewis Hay III, the company’s CEO from 2001 to 2012, told Bloomberg News last year. “We had the scale to buy the equipment cheaper than anybody else. Because we did more wind farms, we just got very, very good at constructing them and operating them.”

Florida Power & Light still exists, serving more than 10 million people across the state, but it’s now part of a larger NextEra whose reach extends far beyond Florida. Robo was named CEO in 2012. A Harvard Business School graduate, he rarely gives interviews. Hay describes him as a quick thinker with an “incredible” memory for details. When presented with a project, Hay says, Robo can quickly go through it and “usually come up with half a thousand ideas on how to make it a better project very quickly.”

NextEra is among the industry titans backing the formation of an American advocacy group to lobby for multiple renewables sectors, not just a single one like wind or solar. Biden’s victory makes the timing seem right.

The next president may well have to use executive action if the Democrats fail to take control of the Senate in the pair of Georgia runoff elections in January. But Biden is still expected to accelerate renewable deployment, both to fight climate change and to generate jobs. NextEra’s renewable arm, NextEra Energy Resources, had about 5,000 employees by the end of 2019, not counting construction jobs for new projects—information the company doesn’t disclose. Spokesman Reuter will say that NextEra has enough projects in the pipeline to generate 15 gigawatts of electricity, enough for 11 million homes. That backlog is “larger than our current renewables portfolio, which gives you a sense of just how much work will be executed in the coming years,” he says.

“Certainly, NextEra is going to be one of the—if not the—biggest player in the development of new renewables,” Konolige says. “It’d be hard for anybody to radically displace them.”—With Brian Eckhouse