Australia’s Energy Mess Drives Users Off the Grid

When politics and infighting cause a dramatic government failure, it’s not unusual for the private sector to step in and provide a superior service.

That’s what happened in Somalia’s telecommunications industry in recent decades, where mobile providers offer some of Africa’s lowest call rates despite the absence of a functioning national government since 1991.

It’s not what you’d expect to see in the electricity sector of one of the world’s richest countries and biggest energy exporters. But it’s happening in Australia, a nation whoseresource wealth is matched only by the incompetence of successive governments in managing this blessing.

Monday brought a fresh sign of the policy paralysis as Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull — who once staked and lost his leadership of the Liberal Party on his commitment to climate change — dropped plans for a carbon emissions target from the National Energy Guarantee, or NEG. That decision may or may not have given him a brief respite from threats to his leadership by members of his own party. Either way, it’s unlikely to revive the prospects of the NEG itself, which is probably doomed.

How are electricity users reacting to this policy vacuum? Increasingly, by turning their backs on the grid.

The country’s fastest-growing form of energy generation isn’t wind farms, utility-scale solar parks, gas peakers or even coal plants (which even most utilities admit will never be built again in the country), but so-called behind-the-meter generation — mainly solar panels on private buildings and, increasingly, lithium-ion batteries to back them up.

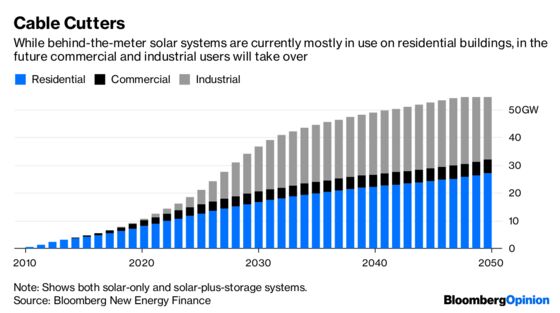

By 2040, such systems will supply about 23 percent of Australia’s electricity demand, with capacity of about 44 gigawatts, according to Annabel Wilton, an analyst for Bloomberg New Energy Finance. That’s roughly equivalent to the capacity supplying the country’s entire main grid at present.

While uptake to date has primarily been from residential customers, future installations will increasingly come from commercial buildings and large industrial facilities.

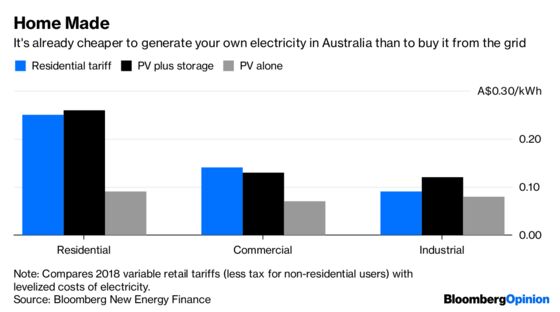

Their decisions are being driven not by altruism but by cold commercial logic. Thanks to the slumping price of renewable generation, existing subsidies for small-scale renewable installations, and Australia’s high wholesale electricity prices, solar systems already provide electricity for less than the cost of buying it from the grid almost everywhere.

Owners of such systems only capture the full benefit if they consume all their electricity when the sun is shining and they’re generating — but the costs of battery backup have been falling so fast that there, too, “socket parity” is rapidly approaching, making the prospect of near-full-time cord-cutting increasingly viable.

For commercial users (chiefly shops and offices), socket parity for solar-plus-storage systems will probably be reached some time this year, and across most of the country residential users will reach the same point by 2020, with large industrial users following later that decade, according to Wilton’s forecasts.

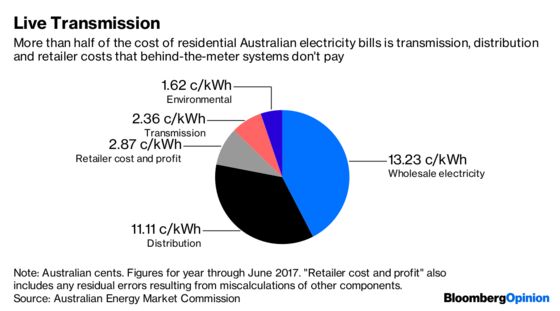

There’s certainly a logic to this shift. More than half of the price of electricity to Australian households comes from transmission, distribution and retailer costs that you’re not paying if you stick panels on your roof and a battery next to your boiler. As a result, even if the small-scale renewable subsidy is phased out, as the government’s antitrust regulator has recommended, it’s unlikely to be more than a temporary setback to the growing competitiveness of self-generation.

While this is one path to a lower-carbon future for Australian electricity, in many ways it’s a terrible sign of market failure. Small-scale renewable systems are typically higher-cost than utility-scale ones. They also operate for a shorter portion of the day and are less likely to integrate neatly with the existing grid. About one-third of rooftop solar generation in 2050 — some 26 terawatt-hours — will be getting fed back into the network, with no very obvious plans about how those spare electrons are going to be used.

A better-designed system would see more power from utility-scale renewables whose capacity and generation was modeled for a better fit with demand forecasts. But for that to happen, investors would need the confidence to invest in such facilities.

Years of muddled energy policies mean such confidence these days is sorely lacking. If Australia manages to decarbonize its electricity sector over the decades ahead, it won’t be because of the government, but in spite of it.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

David Fickling is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering commodities, as well as industrial and consumer companies. He has been a reporter for Bloomberg News, Dow Jones, the Wall Street Journal, the Financial Times and the Guardian.