Electric Ridesharing Benefits the Grid, and EVgo Has the Data to Prove It

Rideshare services like Uber and Lyft are offering more electric vehicles, boosting the need for fast charging. That may help the grid in high-solar states like California.

Electric-vehicle charging at scale could be a blessing or a curse for the grid.

In the best-case scenario, plug-in vehicles charge up at times that align with needs of the power grid. In the worst case, they strain the system, creating a new challenge for grid operators.

Julie Blunden, executive vice president at fast-charging network operator EVgo, insists the former case is the correct one. What’s more, she said, “I can show you the data.”

“Now that we’re legitimately bringing in transportation electrification, not as a hypothetical, but with operational data…it is definitive that we have great benefits at the scale of gigawatt-hours,” she said.

The data around EV fleets, as opposed to personal vehicles, is particularly interesting to EVgo because of how many miles these vehicles travel, and thus how much charging they need.

In 2018, EVgo increased the volume of electric miles powered on its fast charging network by 88 percent compared to the previous year, charging more than 75 million miles through its public network of more than 1,100 DC fast chargers across 34 states. More than a third of those miles were from light-duty vehicles (LDV) fleets, comprising rideshare, carshare and delivery vehicles.

This is just the beginning. Ridesharing services such as Uber, Lyft and Maven are seeing increased EV adoption across their fleets — driven largely by their own internal efforts, but increasingly due to policy pressures.

In California, where there are already more than half a million EVs plugging in, this trend could appear daunting to the state grid operator. But when EVgo crunched its data, the company says it found a “demonstrable and material” benefit to the grid.

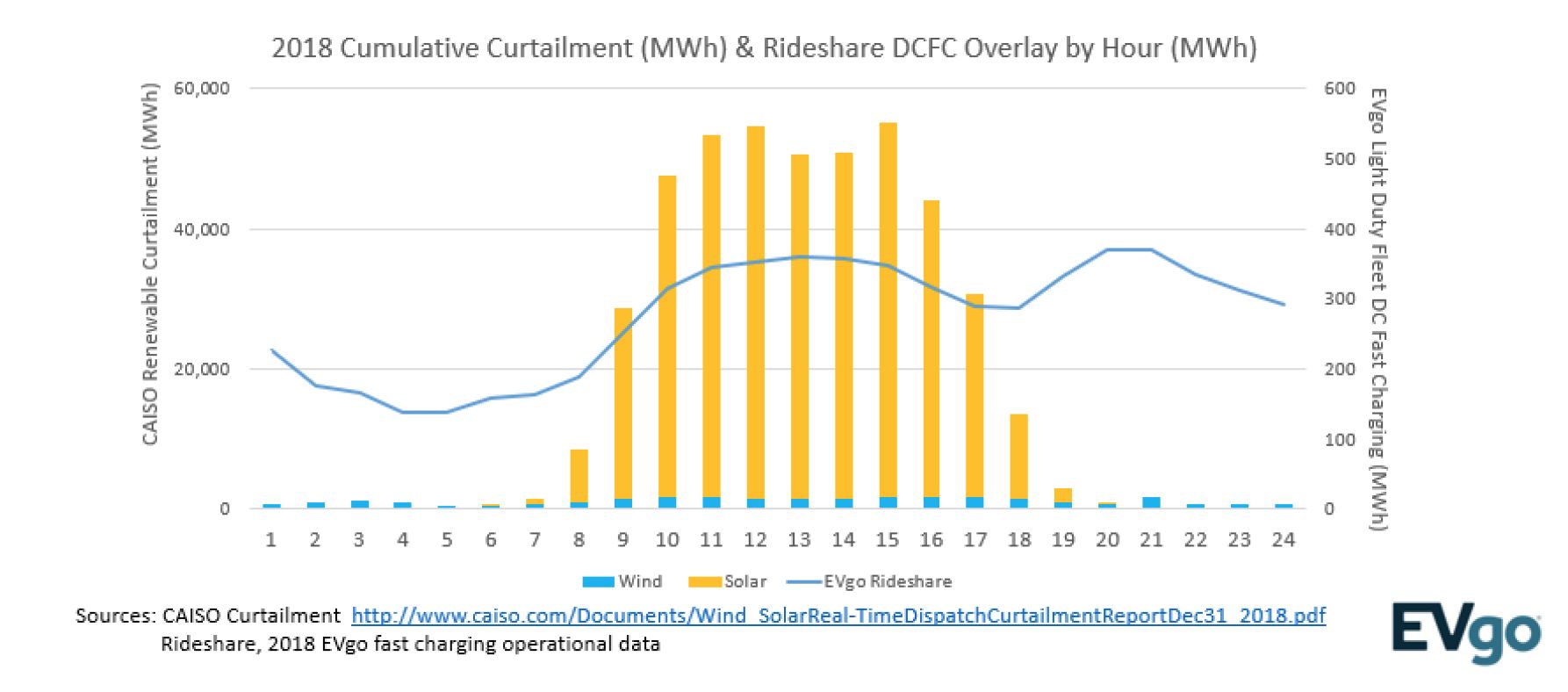

Specifically, EVgo found that the cumulative annual load profile by hour of LDV fleets using its fast charging network — with rideshare vehicles currently making up the lion’s share on a gigawatt-hour basis — aligns with the cumulative solar curtailment by hour on the CAISO system.

The chart above shows how EVgo’s cumulative 2018 LDV fleet fast-charging (in megawatt-hours) aligns with the cumulative CAISO renewable curtailment (in gigawatt-hours).

“Fundamentally, LDV fleet drivers seek to maximize driving time and revenue during the morning and evening rush hours and maximize charging midday and at night,” according to an EVgo brief. As a result, more than 45 percent of LDV fleet fast-charging was performed during peak solar hours from 9 a.m. through 3 p.m., with more than 30 percent of charging during nighttime hours from 8 p.m. through the 4 a.m. hour, according to EVgo’s analysis.

This means that light-duty fleet vehicles are using up excess solar power generated during the middle of the day that would otherwise be thrown away. All in all, LDV fleets on EVgo’s public network in California reduced midday renewable energy curtailment by gigawatt-hours, according to EVgo’s analysis.

In related news, EVgo announced this week it has contracted for 100 percent renewable energy to power its fast-charging network, “to ensure that each gigawatt-hour delivered on its fast-charging network financially supports an operating renewable energy generator in the U.S.”

Mitigating the duck curve

By charging up in the middle of the day, LDV fleets on EVgo’s network also help to address the duck curve — where midday net load drops, driven by lots of solar flooding onto the grid, before a steep ramp-up in the late afternoon and evening, as solar generation fades and people come home from work and increase their electricity use. Managing the duck curve in the late afternoon is one of the most challenging tasks for a grid operator.

EV fleets help mitigate this issue by reducing the depth of the duck’s “belly.” Personal vehicle charging habits aren’t consistent and predictable, according to EVgo, so the impact is less pronounced.

Furthermore, the fleet-charging benefits occurred on EVgo’s network without the use of price signals to align charging times with grid needs, which suggests there could be an opportunity to improve the fleet fast-charging profile even further.

A spokesperson for California’s Independent System Operator (CAISO) noted that the ISO has identified EVs as one of the key strategies for solving oversupply and curtailments, as outlined on its Managing Oversupply webpage.

“To be effective, the charging needs to be well timed and well placed,” she said. “Because of their ability to preset scheduled and/or price signal charging options, electric vehicles are well positioned to quickly and reliably provide an automated response to rates in a way that reflects system needs.”

That’s precisely the case EVgo is looking to make.

“What we can tell you definitively is that fast-charging is offering the kind of service, particularly to a segment like light-duty vehicle fleets, that is incredibly well aligned to avoid solar curtailment. That’s a beautiful thing. That’s a benefit to all.”

“You multiply that by two, and then by five, and then by 10 over the next few years,” she added, “and you start to realize what we’re really talking about is going to become quite a material benefit.”

Ridesharing goes electric

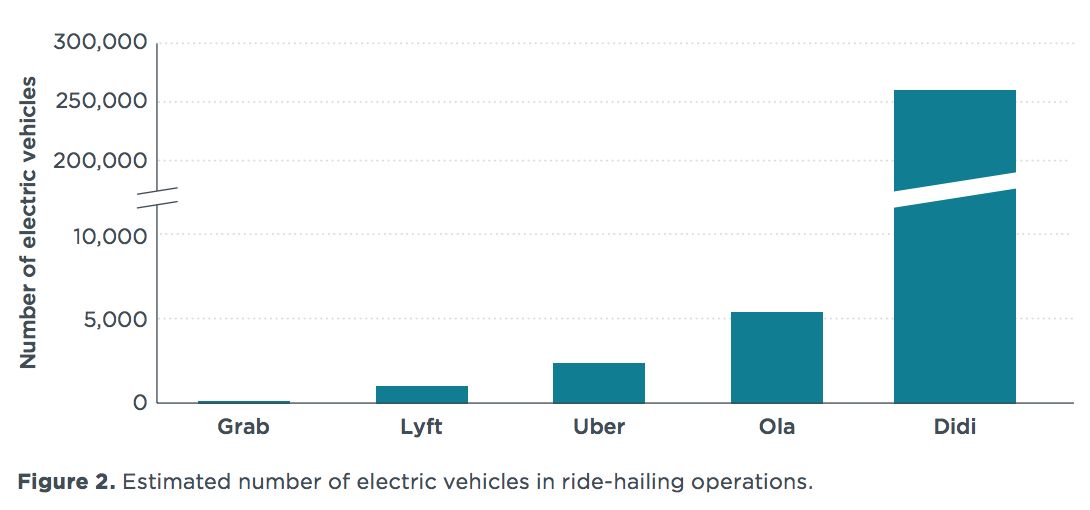

There are relatively few EVs in the U.S. ridesharing fleet today. According to a the International Council on Clean Transportation (ICCT), less than 0.2 percent of vehicles used for Uber and Lyft were electric at the end of 2017, with fewer than 10,000 EVs used in U.S. ride-hailing applications overall.

But that number is on track to see significant growth.

Ride-Hailing EV Adoption Through 2017

In California, policymakers have taken several steps in recent months to encourage a shift to electric ridesharing. Most notably, then-Governor Jerry Brown last fall signed into law SB 1014, which encourages rapid electrification of LDV fleets.

The bill specifically directs the California Air Resources Board and the California Public Utilities Commission to adopt and implement two targets: one to increase the deployment of zero-emission vehicles by transportation network companies, such as Uber and Lyft, and one to reduce greenhouse gas emissions per passenger mile.

At the city level, Mayor Eric Garcetti’s recently announced Green New Deal for Los Angeles calls for 80 percent of the vehicles in L.A. to be powered by electricity or zero-emissions fuels by 2035. Under that broader transportation target, the plan calls for developing “a suite of incentives for electric autonomous shared vehicles, and electric car and rideshare overall.” It also calls for a major deployment of publicly available EV charging stations in order to serve those vehicles.

Companies are also taking transformation electrification into their own hands. Last September, Uber announced a $10 million “sustainable mobility” fund and is currently working to boost EV adoption among drivers with partners in a number of cities. Lyft, meanwhile, has introduced a “green mode” to let passengers request EVs and hybrids in hopes of channeling consumer demand for cleaner vehicles and encouraging more drivers to adopt them.

Meanwhile, the top two ride-hailing companies are expected to face increased pressure from shareholder activists to go green in the wake of their IPOs, which could accelerate the pace of EV adoption in their fleets.

General Motors is also getting in on the action. The company’s Maven Gig service provides short-term rentals of GM vehicles, including EVs, for use by rideshare, delivery and other drivers. EVgo launched a partnership with GM in 2017 to provide fast-charging access to Maven drivers, for whom home charging is not always an option and speed is paramount to avoid lost potential revenue.

According to EVgo, the scale and breadth of Maven Gig’s deployments of Chevy Bolts into LDV fleets has had a “massive impact” on the company’s fast-charging network. While EVgo is working with a number of other smaller LDV fleet partners across the U.S., Maven vehicles increased the total of LDV fleet miles fast-charged on EVgo’s network last year to more than 25 million.

Keeping up with the pace

The challenge, says Blunden, is deploying fast-charging stations rapidly enough to serve this spike in electric ridesharing applications.

In fact, light-duty EV fleets are now reaching a high enough penetration level that they’re starting to conflict with personal-use vehicle charging, jamming up EVgo stations. As a result, the company has started building more mixed-use and fleet-dedicated charging stations to prevent lines from forming.

Last month in Los Angeles, EVgo and GM’s Maven unveiled what they claim is the first public-rideshare EV fast-charging hub in the nation. The Venice Crossroads charging hub features a total of nine 50-kilowatt DC fast chargers, including seven dedicated for Maven Gig members and two chargers available for all EV drivers.

EVgo currently has a “couple hundred” EV chargers in its construction pipeline and several hundred more moving toward construction in the next quarter, said Blunden. But even with new charging models and new stations on the way, there’s still a need for more.

“We’re building as fast as we can,” she said, “and it’s not fast enough.”

According to EVgo’s 2018 analysis, more than 20,000 fast chargers will be needed in U.S. metropolitan areas to meet demand for both personal use and LDV fleets by 2025. Combined with EVgo’s data on LDV charging patterns, adding more fast charging to the grid will “help the overall exercise of…balancing generation and demand,” said Blunden.

EVgo and rideshare companies hope that policymakers see this benefit — and have shared their 2018 data with decision-makers across California to ensure that they do — and offer more funding for charging infrastructure as a result.

“As we have learned with Maven Gig, there is a tremendous opportunity that exists combining high-mileage, shared-use EV fleets with the opportunities and needs of the electric grid,” said Alex Keros, smart cities chief at GM Urban Mobility/Maven, in an emailed statement.

“We’re encouraged that this new study shines a light on the tangible environmental and economic benefits of these shared EV fleets, including reducing solar curtailment and cutting greenhouse gas emissions.”

Cal Lankton, vice president of infrastructure operations at Lyft, echoed this sentiment, adding: “We hope that this enables organizations to expand charging infrastructure across the country to support EV drivers on the platform, especially fast charging infrastructure in urban areas.”

EVgo’s analysis finds that the rise of EVs for ridesharing means that there’s going to be a greater need for EV charging than previously thought, but just how much more remains a point of contention.

Just how much charging is needed?

Based on EVgo data for 2018, the company believes projections in a recent benchmarking report on the U.S. “charging gap” fall short.

A January 2019 report from ICCT found that 10,000 DC fast chargers (DCFC) will be required, out of a total needed 195,000 chargers, across the 100 most populous U.S. metropolitan areas by 2025. But EVgo believes that number should be doubled.

“By adding a conservative forecast of 100,000 LDV operating as fleets in car share, rideshare and delivery, among other purposes, in 2025, and a 10:1 LDV fleet to DCFC ratio, demand would increase by an additional 10,000 fast chargers” — for a total of 20,000 new fast chargers needed nationwide — the EVgo study states.

The discrepancy between projections is due partly to the fact that ICCT’s forecast was based on figures from 2017, the charging company argues. But Nic Lutsey, EV program director at ICCT, isn’t convinced that the gap is so great.

For one thing, automakers are manufacturing EV models for different vehicle classes at given volumes and at a certain rate, which “fundamentally restricts how fast all of this can happen,” he said in an interview.

Even if EV access isn’t a limitation, ridesharing fleets have so far been electrifying slower than the vehicle fleet overall. Based on ICCT’s analysis, ride-hailing companies electrified their fleets at one-third the rate of the private market from 2012 to 2017.

“So, those two factors: How many EVs in total there are, and how rapidly ride-hailing is electrifying, really prevent us from making any serious forecast to say how much charging would we need per all the ride-hailing,” Lutsey said, “because it remains to be seen whether policy or the business cases of the ride-hailing companies will really drive them to electrify in the next 10 to 15 years.”

EVgo would argue that the business case is there, and that adoption rates are about to spike based on new data from 2018. The ICCT’s own reports acknowledge that ridesharing is a wild card in projecting future charging needs.

Lutsey is hesitant to change his outlook just yet.

“The only part that might change our thinking is if 2018 showed a bunch of data that said the ride-hailing companies are electrifying at a much faster rate,” he said. “I’d be very skeptical…on that being actually the case, because we do try to track all the pilot programs that Uber and Lyft are doing.”

But he admitted that in the event that ride-hailing fleets really do take off, “that could certainly increase the need for DC fast charging in particular, much higher than what we’re projecting here.”