Recently, Kotak Mahindra Bank finalised an agreement to provide end-user finance to Simpa Networks, which has more than 65,000 rural customers and was recently acquired by French energy giant ENGIE

New Delhi: Solar companies serving rural consumers and businesses have struggled to raise affordable and long-term commercial debt for scaling, despite a national target of 40 gigawatt (GW) of rooftop solar and 500 megawatt (MW) of green mini-grids. While capital is still inadequate, banks are starting to see the promise of this huge market and are considering innovative ways to accelerate growth.

Debt is essential for distributed renewables: Project finance for mini-grids, working capital and end-user financing for rooftops, solar pumps and solar home systems. But, it has been largely missing from the sector, especially for “last-mile” communities.

Company executives cite three primary reasons: Technologies and business models are new so the risks are not fully understood by lending institutions; rural consumers lack credit histories; and the ticket size of individual loans and overall portfolios is still small, making it less attractive for mainstream lenders who find it easier to deploy larger ticket sizes in more mature sectors.

However, the comfort level at banks is increasing. Recently, Kotak Mahindra Bank finalised an agreement to provide end-user finance to Simpa Networks, which has more than 65,000 rural customers and was recently acquired by French energy giant ENGIE.

Simpa Networks’ innovative solar financing model for home and business had already attracted RBL Bank’s support from a $75 million loan guarantee programme that the bank launched with the support of USAID. The RBL-Simpa partnership has so far resulted in 8,000-9,000 households being solarised in Uttar Pradesh, according to RBL.

“We expect that increasing scale in the sector, increasing familiarity of lenders with the sector and innovative financing structures will catalyse new financing into distributed solar,” said Piyush Mathur, CEO, Simpa Networks.

In July, the state-owned India Renewable Energy Development Agency (IREDA) provided debt to the sector from a $20-million fund. It made a seven-year loan to Kolkata-based mini-grid developer, Mlinda, to cover 25 per cent of the capital expenditure for building four projects in Jharkhand.

But total debt for rural solar, while growing, is still limited and mostly coming from just a few larger entities.

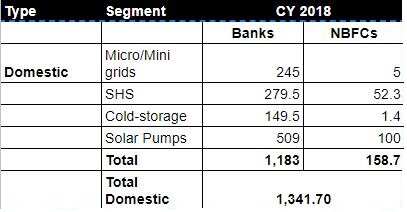

Decentralised renewable energy debt-financing in India

The table below captures the sub-segment wise debt-financing details (in rupee million) for DRE segment in India. Please note that the numbers are for pure-play DRE enterprises only

In a Climate Policy Initiative (CPI) report, the International Finance Corporation had estimated that India will need $450 billion to finance its 2030 clean energy targets, with debt funding requirements expected to be about 70 per cent of that — or $315 billion.

According to management consulting firm, cKinetics, debt from domestic financial institutions for pure-play decentralised renewable energy companies has gone from being non-existent in 2014 to about Rs 1.34 billion ($19 million) in 2018. Financial intermediary, Mynergy, estimated that such firms are currently seeking at least another $20 million in debt. According to cKinetics, end-user finance needed for the solar irrigation scheme, KUSUM, alone was about $700 million.

“The engagement of domestic financiers, both banks and non-banking finance companies (NBFCs) is key to unleashing the potential for catalytic change. Risk mitigation mechanisms and collaborative partnerships between banks and NBFCs is the fastest way to help drive understanding on the credit worthiness of upcoming players and ensure competitively priced, adequate capital is available,” said Upendra Bhatt, managing director, cKinetics.

According to the CPI report, there is an opportunity to create a viable path in increasing access to debt through aggregation of renewable energy project loans, either big or small. It added that a financial institution like IREDA could bundle multiple projects and increase the size of issuance through a so-called Alternative Investment Fund. Such a fund would be an interim step towards green bonds through securitisation, which is currently difficult as it requires both aggregation and credit enhancement.

“India’s potential for rooftop solar is 400 GW, the target is 40 GW, yet we’ve only reached 4-5 GW. The potential is not being realised. In terms of clean energy exposure, banks are already reaching their limits on risk and we need to shift exposure to capital markets,” said Dhruba Purkayastha, director of CPI’s US-India Clean Energy Finance initiative.

A number of microfinance companies have been looking at the rural solar market with anticipation, but their high cost of capital has been a barrier for companies seeking finance.

With many of the specialist lenders and microfinance companies now turning into small finance banks (SFBs) and accessing retail deposits to reduce their cost of capital, a fresh opportunity is opening up for companies to partner with SFBs.

Bengaluru-based not-for-profit, SELCO Foundation, is working towards sensitising lending institutions to the opportunity in financing distributed solar. It is working with Syndicate Bank, Odisha Gramya Bank, Narmada Jhabua Gramin Bank, and Bihar Gramin Bank to establish end-user loan and other innovative financing activities. It is also working with banks to introduce a clean energy financing component into their internal training programmes in order to make distributed renewable energy an important portfolio for bank financing in rural areas.

According to IFC estimates, in order to meet its 2030 clean energy targets, India will need $450 billion in finance. Debt, as a temporary repayable form of capital, has a special role to play in scaling up DRE. By spreading the burden over a period of time, debt-financing helps correct the mismatch between high upfront capital costs and the corresponding benefits that accrue over the period of use, which makes it easier for users and enterprises to commit.

Disclaimer: This article is part of a series titled Energizing Rural India under an editorial partnership between ETEnergyworld and Power for All