It can be hard to get your head around just how much energy the world uses. Expressed in terms of oil, it was equivalent to almost 14 billion metric tons of the stuff in 2017. That’s like burning through all of Russia’s proved reserves in the space of 12 months, which is, in technical terms, a lot.

But there’s an even trickier issue to ponder: What does it even mean to “use” energy? Granted, that sounds like something you might hear from a stoner at the engineering faculty. But it’s an increasingly important question as renewable energy and electrification expand.

Harry Benham, an oil-industry veteran who now runs Carbury Consulting, wrote an elegant blog post this summer about the fundamental difference between thermal energy — mostly from burning stuff or splitting atoms — and what he calls the “universal energy” captured in wind and solar power. While earlier shifts, such as swapping wood for coal, are often called energy transitions, they were really substitutions of one thermal source to another. But wind and solar “are different energies in kind, not degree.”

The big thing here is waste. Broadly speaking, when you burn a gallon of gasoline, perhaps only a quarter of the energy released actually goes into turning the wheels. The rest is wasted, mostly as heat. In other words, you buy roughly four gallons of gasoline to get the useful energy of one. Renewable energy doesn’t work that way, with wind turbines or solar arrays effectively capturing energy from the ether. Yes, they only convert a portion of the energy hitting them into electricity, but that energy is infinite and hasn’t had to be mined or pumped and transported.

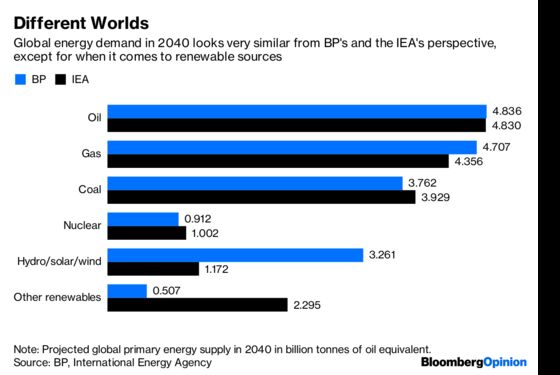

This presents an apples-and oranges-problem for statisticians. Here are projections of global primary energy demand in 2040 from BP Plc and the International Energy Agency:

The estimates for thermal energy from fossil fuels and nuclear power are very similar. The “other renewables” bars are different largely because BP excludes some non-traded fuels that the IEA measures.

The really interesting difference concerns hydro, solar and wind power. BP’s higher figure isn’t because it is more bullish on these. Rather, in order to make the renewables figures comparable with the ones for fossil fuels and nuclear power, BP grosses them up as if they also produced waste energy. The IEA doesn’t do this, so its figure represents just the energy derived from a solar panel, wind turbine, or hydro plant. The IEA figure is 36 percent of the BP one, similar to the 38 percent conversion factor BP uses to adjust the data.

There are pros and cons to both approaches. The IEA’s reflects the fundamentally different nature of renewable energy, but at the cost of making its share of the market look very low: Solar and wind are 11 percent of BP’s mix in 2040 but less than 4 percent of the IEA’s.

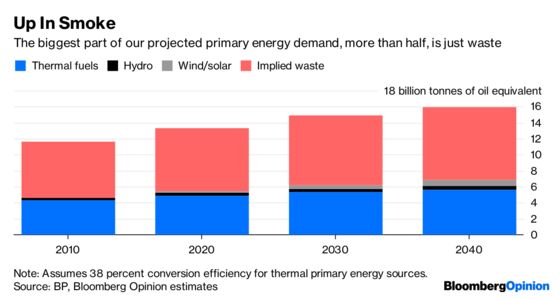

By far the biggest element in both forecasts, though, is the one you can’t see: waste.

Here are BP’s projections, but with a few adjustments. First, I’ve grouped them into thermal sources (oil, gas, coal, nuclear, biomass and biofuels), hydro power, and wind and solar power. Then, I’ve assumed a flat conversion efficiency of 38 percent for the thermal sources (i.e., the amount of useful energy they produce). This is in line with BP’s assumed average for thermal power plants and is used across the board for the sake of simplicity:

The numbers aren’t exact, but the picture is clear: Perhaps 60-70 percent of what we call primary energy isn’t usefully consumed at all.

That’s a moot point when fossil fuels plus nuclear power dominate. Their sheer energy density (the power they pack into a small volume) combined with, in the case of fossil fuels, inconsistent or absent pricing of greenhouse-gas emissions, has made them dominant. Waste heat just comes with the territory.

But as renewable energy falls in cost and makes inroads, especially in conjunction with increased electrification of things like heating and transportation, it becomes a far more interesting issue. Consider an electric car being charged mostly with power from renewable sources. If it replaces a car running on gasoline, then it doesn’t just displace the useful gallon turning the wheels, but also the other three that were just making the radiator do its job.

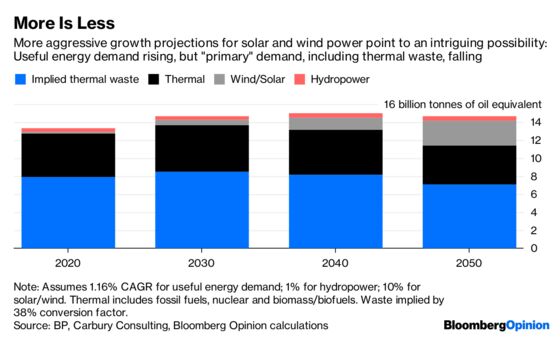

In his blog post, Benham proposed a thought experiment, shifting some estimates around on energy consumption and the growth of solar and wind power. Using my broad assumption on conversion, BP’s projections imply useful energy demand — that is, excluding the implied waste — growing by almost 1.2 percent a year from 2020 to 2040. Hydro power grows by about 1 percent a year (it’s hard to build dams everywhere) and solar and wind together by an average of just under 7 percent a year (front-loaded and down from 20 percent in the previous decade).

Now plug in more aggressive numbers for wind and solar, growing at an average of 10 percent instead through 2040 and dropping to 7 percent in the next decade (leaving everything else unchanged):

In case it needs to be said, this isn’t supposed to be an accurate picture of the future. The point is to show how renewable energy, at higher penetration, subverts the way we think about the world’s energy consumption. By displacing not only useful thermal energy but also the waste, renewable sources add to the overall level of useful energy while simultaneously slowing and even reversing the growth in primary energy consumption.

A growing world economy and population coupled with flat or even falling primary energy demand might seem paradoxical. But we’ve seen it happen already in the U.S. and some other countries (see this recent analysis by Nikos Tsafos at the Center for Strategic & International Studies).

At the very least, the rise of renewable sources means we should be thinking about “useful energy” as a way of adding up our needs rather than just “primary energy.” Competition from renewable technologies, coupled with higher electrification, represents a decisive break with the past. All that primary energy that isn’t actually being used is like a target on the incumbent system’s back; especially as, for some fuels, it also serves as a metaphor for more pernicious forms of waste, such as carbon dioxide. As with any other industry, such excess invites disruption.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Liam Denning is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering energy, mining and commodities. He previously was editor of the Wall Street Journal’s Heard on the Street column and wrote for the Financial Times’ Lex column. He was also an investment banker.