IEEFA India: Something short of an ‘amazing opportunity’ for U.S. coal

Exporters will likely be disappointed at a policy- and cost-driven decline in important demand

If this is the case, then the energy secretary is mistaken.

Granted, U.S. coal exports surged in 2017 mostly on demand from Asia. Thermal coal—used for power generation as opposed to metallurgical manufacturing purposes — accounted for most of that increase. India was the No. 1 destination.

And it’s also true that India will continue to import metallurgical coal for the foreseeable future due to a lack of sufficient suitable domestic reserves, even with the state-owned Coal India in 2017 announcing a target to halve metallurgical imports by 2030.

However, in the long -term, India will cease to be a thermal coal export destination for any country, the U.S. included.

While the International Energy Agency (IEA) in its most recent World Energy Outlook has India’s coal imports rising 72 million tonnes coal equivalent (Mtce) to 235Mtce by 2040, that forecast should qualified on a couple of points.

First, the IEA projects that three-quarters of the increase will be driven by metallurgical coal. Second, the agency has left itself plenty of wiggle room for change.

There’s also the fact that the IEA outlook, dated 2017, uses 2016 renewable energy installation data to assess the India’s renewables trajectory, noting that solar-PV capacity increased 80% to 9 GW in that calendar year alone.

The agency also concedes that a faster-than-expected drop in solar costs going forward would “result in significant upside potential for solar PV and downside for coal.”

SO THE IEA WILL VERY LIKELY HAVE TO DECREASE ITS THERMAL COAL IMPORT PROJECTION FOR INDIA its next annual outlook report based simply on the fact that 2017 was a landmark year for Indian renewables.

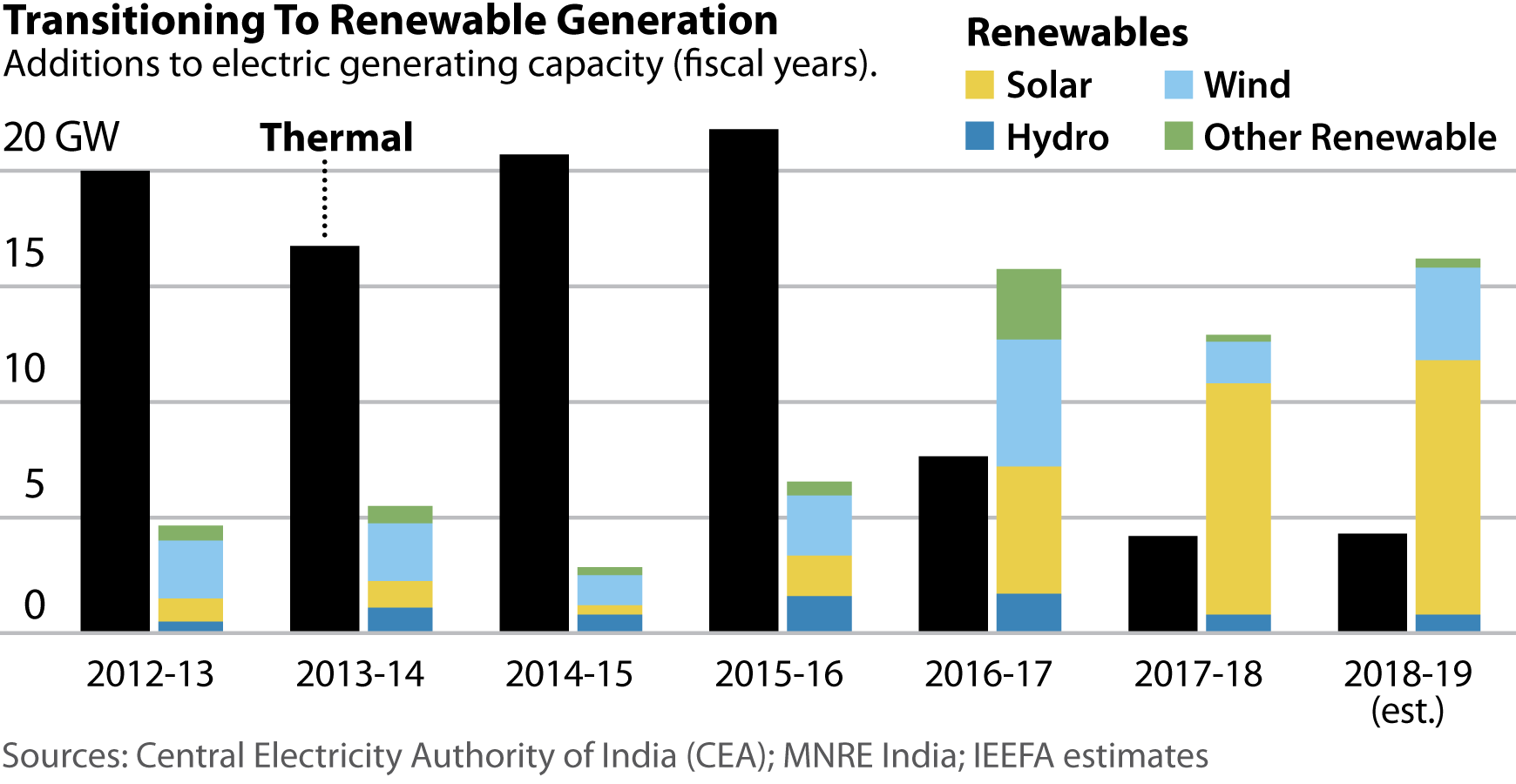

Last year saw such large reductions in the cost of Indian solar PV and wind power that such renewables are now cheaper than existing domestic coal-fired power. The Indian fiscal year that ended in March 2017 was the first one in which combined renewables installations outpaced coal-fired power construction (with net thermal installs falling 65% year on year to a decade-low 7.7 GW).

The following fiscal year, from April 2017 to March 2018, saw net thermal installs of just 4.2 GW (down an additional 46% year on year) and the addition of more solar PV capacity than all other technologies combined, with a total of 10.4 GW.

In this fiscal year, India has only expanded its renewables ambitions. Power Minister R. K. Singh announced recently the possibility of a 100 GW solar tender program. Although no details have been released as to how such a program would work, it is in line and with an announcement by Japan’s SoftBank that it intends to invest US$60-100 billion in Indian solar.

The India government has also recently announced a move into offshore wind, with a total installed-capacity target of 30 GW by 2030.

The IEA’s overly optimistic view of Indian coal imports is rooted partly in the agency’s assertion that, “For the moment, imports appear to be the cheapest supply option along most of India’s western coastline.”

Since that statement was published, things have turned increasingly sour for Indian west-coast power plants that run on imported coal.

The two largest coal-fired power plants in India, the Mundra power stations owned by Tata Power and Adani Power have proven to be economically unviable due to the doubling of imported coal prices since 2016. Tata Power has stated that it will aim to fuel 50% of its plant’s generation, designed for imported coal, with domestic coal in move IEEFA estimates would reduce its fuel costs by over US$150m annually relative to current spot prices.

Meanwhile, Adani Power has turned off most of the units at its Mundra plant, as it is cheaper to incur a penalty for breach of power purchase agreement than lose money on every kilowatt hour generated. Adani Power Mundra may now seek bankruptcy protection, a development that hardly seems to support the IEA’s assertion that India’s west coast may become “a new arbitrage point and price marker for global trade.”

Further, the recently reported fate of a stranded coal-fired plant in Jharkhand state, home to India’s largest coal reserves, shows that it isn’t just plants reliant on imported coal that are in trouble. And last month’s cancellation by NPTC, the state-owned utility, of a 4GW coal plant proposed for Andhra Pradesh supports IEEFA’s view.

Analysts at Bank of America Merrill Lynch have said Indian banks face US$38 billion in losses on bad loans to the coal-fired power sector—a sector that contains the most significant loan risk in India.

With banks unwilling to take loss ratios of up to 75% on their power-sector lending, there is no relief in sight and—under these circumstances—it is not surprising that India’s planned coal power pipeline has shrunk by 547 GW since 2010 — hardly a promising indicator for U.S. coal technology opportunities in India.

Indian government actions that may help improve the financial health of the nation’s power distribution companies by driving increased efficiency of domestic coal production and delivery will only result in even less need for thermal coal imports. India’s electricity generation future, in other words, will be based on cheap renewables and domestic coal, with the Central Electricity Authority continuing to target a cessation of thermal coal imports.

The IEA in its outlook concedes that “A reversal in the projected trend of rising imports is possible if circumstances change” and says such a change “would have significant repercussions for coal exporters around the world.”

Given that India’s coal imports peaked in 2014/15 and have declined nearly every quarter since, IEEFA would contend that those circumstances have changed already.

Simon Nicholas is a Sydney-based IEEFA energy finance analyst.