India makes for the perfect case study to explore the transition towards renewables

s the global energy sector transitions from fossil fuels to renewables, it’s time to discuss the risks. For growing countries, do material supply shortages, import dependence and threats to national energy security lie ahead?

The key purpose of this shift is, of course, to halt the disastrous environmental consequences caused by the mining and burning of the two leading fossil fuels: Coal and oil. Yet, despite coal-based power plants being a major contributor to the emission of carbon dioxide – the greenhouse gas responsible for global warming – coal still generates 40 per cent of the world’s power. Oil, meanwhile, is responsible for 23 per cent of global energy-related carbon emissions, with the transportation sector serving as its primary source of consumption.

A changing landscape

Driven by falling power tariffs and grid parity in many countries, the renewable energy sector has grown rapidly over the past two decades. Twenty-four per cent of the world’s power is currently generated from renewables, which could rise to 30 per cent by 2023, according to the International Energy Agency (IEA).

This includes power from solar photovoltaic (SPV), which grew by a staggering 32 per cent in 2017 – with China leading the way on global SPV capacity additions and installing nearly half of all new capacity over the year – while wind generation increased by 10 per cent.

A similar clean energy trend can be observed in the transformative technologies of the transportation sector, where sale of electric vehicles (EVs) is gathering momentum at an unprecedented rate.

With many experts proposing that EVs will eventually replace internal combustion engines and reduce the dependence of crude oil in the transportation sector, research from Bloomberg reveals that the total number of passenger EVs rised by a million from mid-2014 to 2016 and took only six months to achieve the same growth this year.

Taking into account the significant cost reduction and improved battery performance of modern EVs, the IEA has estimated that there will be somewhere between 125 million to 220 million on the road by 2030.

Markets of “rare earth” and other strategic metals

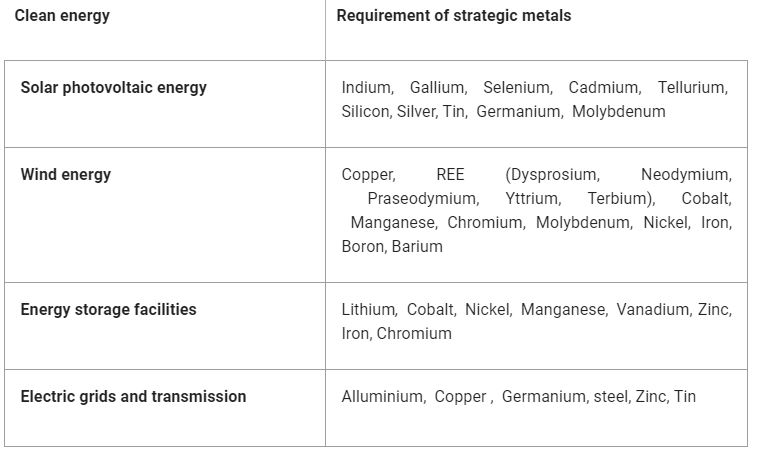

This clean energy revolution has also developed new markets for certain metals and minerals, some of which can be classified in the “rare earth” (REE) category (see table below).

Although, Jamie Speirs and his colleague (2014) observed that some of the strategic metals required for clean energy production experienced exponential growth between 1971-2011 (for example, Gallium 1,800 per cent, Tellurium 900 per cent, Lithium 800 per cent, Cobalt 400 per cent), other global studies suggest an annual 400 per cent to 600 per cent increase in the demand for Gallium, 150 per cent to 380 per cent for Neodymium and 300 per cent for Indium by 2030.

With the need for Lithium and Graphite also predicted to increase five- to seven-fold by 2030, is this growth trail sustainable?

According to the US Geological Survey report, Earth may not have enough reserve bases of these critical metals to sustain future clean energy growth. Another factor is that, just as with crude oil, countries including China, Chile, Congo, Republic of Korea, Russia and Australia enjoy better availability of these metals or minerals in higher concentrations.

Some of these nations being politically categorised as ‘critical’ to ‘very critical’ poses many questions: Are we going to face an OPEC-like cartelisation in clean energy? With a major percentage of these metals being mined or processed in China, could it become a clean energy superpower? What impact will this have on important geographic neighbours such as India?

India’s clean energy push

India makes for the perfect case study to explore the transition towards renewables. The country is gifted with abundant renewable energy (RE) sources, courtesy of its tropical climate, and must harness their potential to replace a part of its inefficient coal-fired power plants.

Meanwhile, the introduction of EVs could alleviate crude oil import dependence (80 per cent of India’s requirement is currently imported) and increase e-mobility, reducing vehicular emissions in Indian cities, the majority of which are critically polluted.

The Indian government has also set lofty targets: Installing 227 gigawatt (GW) of electricity from renewables, with 113 GW coming from solar and another 66.6 GW from wind; and focusing on creating charging infrastructure and a policy framework, so that more than 30 per cent of the vehicles on the roads are electric by 2030. However, does this strategy jeopardise the country’s energy security?

The answer is complex. Not only does India lack a robust manufacturing base for solar cells and associated components, but its solar programme is heavily dependent on imports. Domestic solar cells are 10 per cent to 15 per cent costlier than their Chinese counterparts (where production enjoys cheap capital, subsidised power, land, and other export incentives), meaning, Indian solar manufacturers have less than 10 per cent of the market share.

With 89 per cent of the $3.41 billion worth of solar cells India imported last year from China, and given the tumultuous relationship between these neighbours, such high levels of clean energy import dependence could undoubtedly put the nation’s energy security at risk moving into the future.

Then there is the potential negative impact of clean energy transition on India’s employment. While growing renewable energy technologies can be instrumental for creating new jobs – rising from 9.7 million in 2015 to 10.3 million in 2017, 65 per cent of solar and 44 per cent of wind-related jobs are located in China, according to the International Renewable Energy Agency. A lower dependence on coal-based power means significant job losses in both labour-intensive mining and its downstream industries.

So, what is the solution? India, with world’s fifth-largest coal reserves after USA, Russia, China and Australia, cannot ignore the role of domestic coal in supplying electricity at affordable price, which provides much-needed energy security and employment prospects, alongside grid stability. A judicious mix of coal-based power with HELE (high efficiency low emission) technologies and renewables is the need of the hour.

[Kakali Kanjilal, professor of operations an and statistics at International Management Institute also contributed to this piece]

DISCLAIMER: The views expressed are solely of the author and ETEnergyworld.com does not necessarily subscribe to it. ETEnergyworld.com shall not be responsible for any damage caused to any person/organisation directly or indirectly.