Is solar energy really green? We answer some common questions about panels – EQ Mag Pro

As the world continues to push towards net zero emissions, more large-scale solar farms will be built in Australia.

But why are they being built on productive agricultural land and are how credible are claims about toxic contamination?

The Clean Energy Council (CEC) is forecasting a massive increase in the number of solar panels in the short term.

The amount of solar power installed in Australia has doubled in the past three to four years, and the CEC is forecasting it will double again in the next couple of years.

- The number of solar panels will double in the next two years

- Many large solar projects are being developed on agricultural land

- Regional communities are concerned about heavy metal contamination and lost jobs

Concern is global

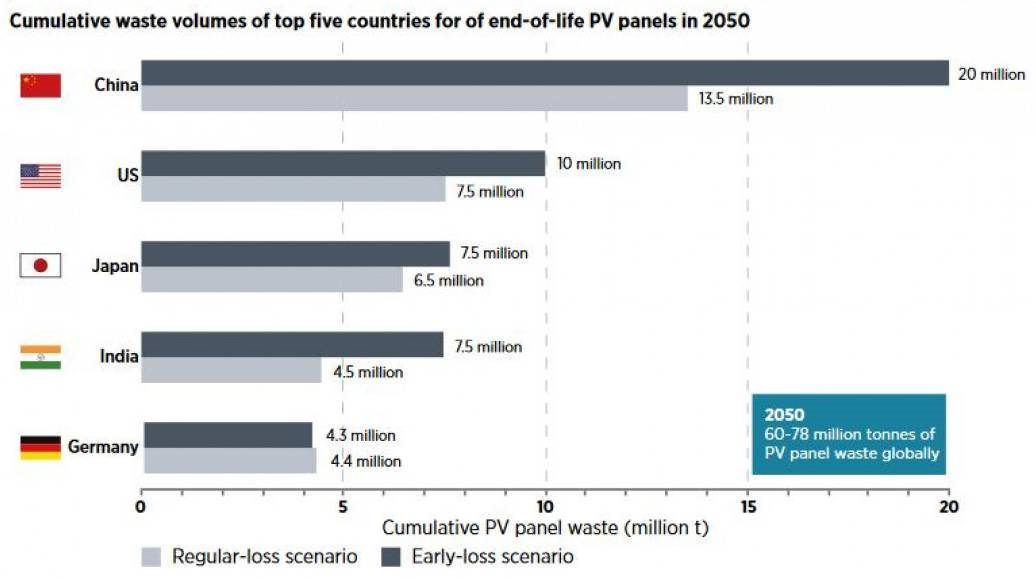

Achim Steiner, administrator of the United Nations Development Program, said solar panels were adding significantly to the world’s non-recycled waste mountain.

“But it also poses a growing threat to human health and the environment due to the hazardous elements it contains,” Mr Steiner said.

Australia is adding to that mountain by sending 40,000 old panels a year in containers to markets in developing countries.

While that trade provides cheap panels for poorer nations, the UN is concerned that many of them will end up in landfill overseas.

Are solar panels toxic?

The vast majority of solar panels are made of thin silicon wafers using refined silicon dioxide.

It is the same chemical compound as sand, which is used in making glass, so it is harmless.

The solar cells are connected by thin strips of tin and copper which is sealed and protected under glass.

Almost all of the materials can be recycled and there are several new plants in development that will be able to turn old panels into reusable materials.

There are, however, a small number of panels that were made in the past using cadmium, which is highly toxic and associated with serious health problems.

Some panels are also made with nitrogen trifluoride (NF3), a gas that is associated with global warming.

A South Korean study from 2020 raised concerns about contamination from solar panels that are “released into the environment during their disposal or following damage, such as that from natural disasters.”

The United States wants to address the problem as well, with a report by the National Renewable Energy Laboratory from March 2021 pointing to a lack of incentives for recycling companies and confusing and conflicting state regulations.

Are solar farms taking over productive farm land?

The NSW government has set up five renewable energy zones in regional areas where it is promoting the development of solar farms close to large populations and the existing electricity grid.

That means productive farming land is sometimes used to build large-scale solar plants, and farmer Bianca Schultz right is in the firing line.

She owns a property next door to the proposed Walla Walla site in the Riverina in south-west NSW, while the Culcairn project borders her other boundary.

Ms Schultz said the property was used in the past for grazing livestock, making hay, and cropping.

She thinks that turning it into an industrial-scale solar plant with just a few employees for maintenance will negatively affect the local economy.

“The on-flow effect on the transport companies, the grain merchants, the rural merchants; it’s taking away a lot from our community,” she said.

Keeping jobs and food

One of the companies behind the projects in the Riverina and eight others across Australia is Fotowatio Renewable Ventures (FRV).

In a report on the Walla Walla project, FRV argued they can maintain up to 85 per cent of the current stocking rates for livestock with the solar farm.

The project will employ 16 people on-site and will generate $200 million during the construction phase, according to an Ernst and Young (EY) study.

EY also published a report highlighting the potential for the renewables industry to lead the world to global recovery, post-pandemic.

Regulator comfortable with solar expansion

Australian Energy Infrastructure Commissioner Andrew Dyer says Australia has plenty of low value land next to the grid that had already cleared, so it suits developments of this kind.

He understands why some farmers would be concerned about losing land for production out of their region, but he gets very few complaints about solar projects in general, especially once they are up and running.

He says there is no evidence to support the heat sink theory and he has had no complaints about cadmium contamination, but he does agree that solar projects need an “end of life” plan and wants to see default setbacks to protect neighbours.

“We have them in the wind industry and there should be setbacks from houses, roads, and other forms of public infrastructure,” he said.

My Dyer is concerned about possible contamination leaking from dumped panels and wants to see sites cleaned up at the end of life.

“Decommissioning plans should include removal of the panels from the site and appropriate disposal so they’re not causing long-term environmental harm,” he said.

Kane Thornton from the industry group the Clean Energy Council says the community broadly supports the growth in renewables, even though there are not many jobs on solar farms once they are built.

“They deliver low-cost power that can support other industries in the region and across the country,” she said.