Merkel’s Natural Gas Bridge Looks Like a Dead End to Executives

Energy executives say the fuel Chancellor Angela Merkel has picked for Germans as a bridge toward a cleaner future could turn out to be another dead end without political guarantees to draw investment.

“I can’t imagine a rational investor who would invest in large-scale gas capacity” without government assurances, said Uniper SE Chief Executive Officer Klaus Schaefer in Berlin this week.

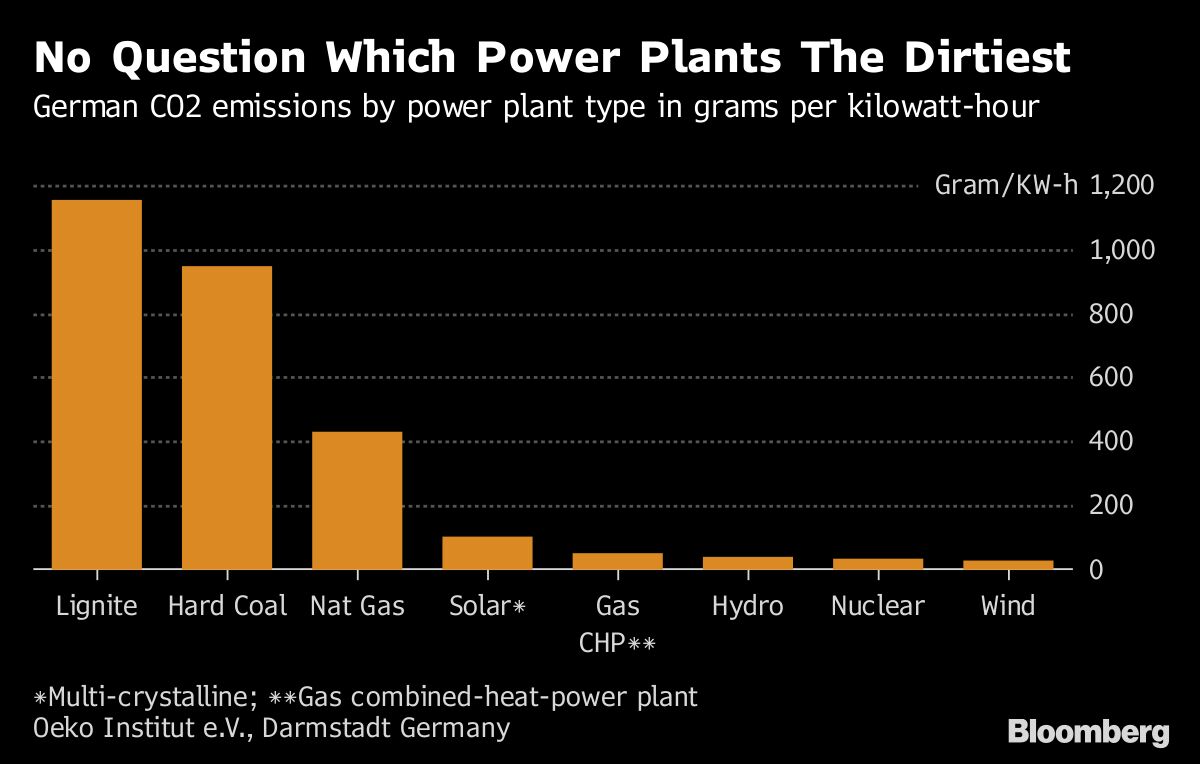

That reticence to invest underscores how difficult it is for German utilities to make money by using the cleanest fossil fuel. Unlike burning coal, which is profitable most of the time, Germany’s gas-fired power plants don’t cross break-even levels, according analysis of spark spreads that show margins for generating electricity from each fuel.

German utilities from RWE AG to Uniper are asking for assurance that the government won’t back track on natural gas as did on nuclear power and is doing with coal. In other nations like the U.K., policy makers have taken measures to ensure gas generators can produce power around the clock and still get paid.

Power companies need to come up with new ways to ensure electricity as coal plants retire and more consumers adopt energy storage to balance against volatile wind and solar generation. Stung by Merkel’s decision to scrap nuclear power and coal plants, utilities are reluctant to invest in gas plants needed to balance the grid unless there’s some sort of guarantee they can make money.

“I guess that the very next day after Germany announces an exit date for coal power — the very next day — there will be calls to phase out gas plants,” Andree Stracke, chief commercial officer of German utility RWE AG’s supply and trading unit, said in London last month.

Industry skepticism over adopting gas could add to the risk of power outages when the last of Germany’s seven nuclear reactors close in 2022. Yet it’s Merkel who billed gas as the fuel that Europe’s biggest economy needs to power an energy transition toward renewables.

Appalled by the meltdown at Japan’s Fukushima reactors in March 2011, Germany hastned its pivot away from traditional generation. Seven years ago, Merkel trumpeted the virtues of gas as safer than nuclear and cleaner than competing fossil fuels, saying gas plants “can be built quickly and are a flexible support for renewable energy” as she signed a deal in Berlin to step up imports from Russia.

Germany’s Economy and Energy Ministry in Berlin didn’t respond to email and phone requests for information on its natural gas power policy.

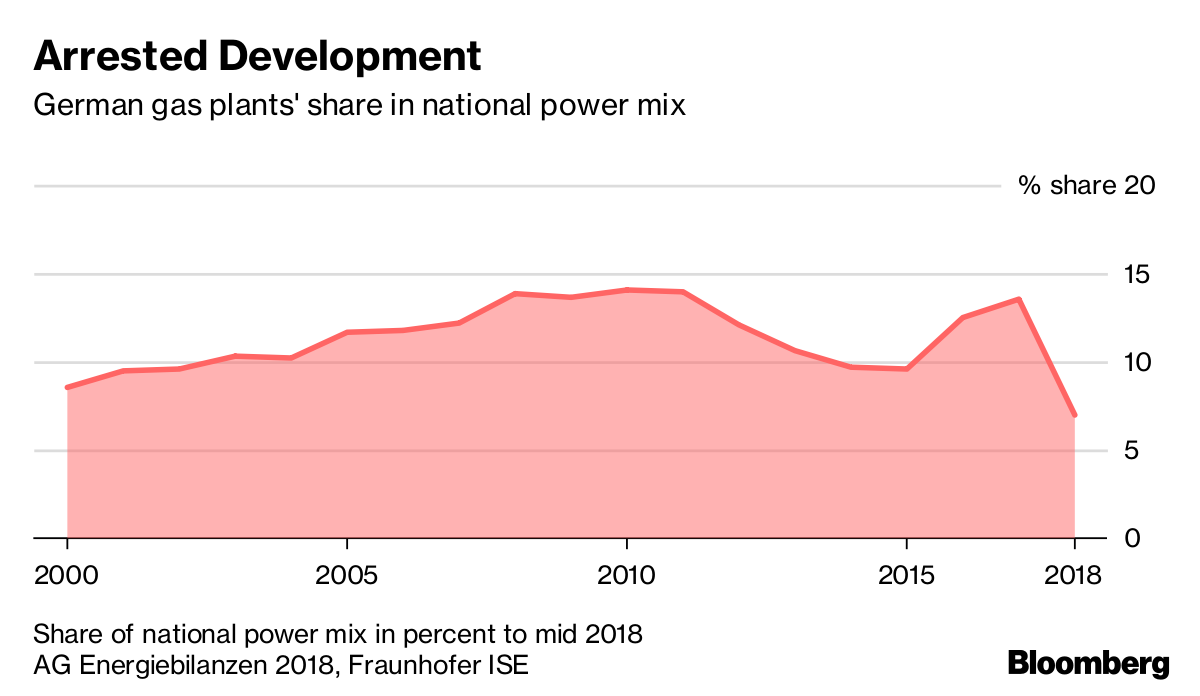

Natural gas still remains stuck with a share of just over 10 percent of the Germany’s power mix, with few signs that it will develop further. No utility is planning new plants for regular operation and modern units such as Statkraft AS’ Knapsack and Herdecke sites near Dortmund sit idle most of the time.

As Merkel’s new coalition has pledged a speedier switch to wind and solar, pushing the share of clean power to 65 percent of total generation by 2030, some utilities have been left wondering whether gas will be needed at all. Recurring supply shortages and plentiful reserves of coal mean German generators are wary of locking in long-term decisions.

A rump portion of coal power, some vested in reserve plants, may stay operational to safeguard baseload and jobs as clean power grows, according to a government commission set up to map out an exit of the fuel. Gas is taking a back seat in the planning.

Utilities like RWE say they sense where the wind is blowing and intend to focus investments on renewable energy, possibly linking cash inputs for new gas plants to auctions of reserve power only, the company’s Chief Financial Officer Markus Krebber told Bloomberg in June.

Some market support for gas plants may be coming as coal plants bear the brunt of costlier pollution permits in the European Union’s Emissions Trading Scheme, according to the BDEW utilities federation in Berlin. About 40 percent of the nation’s carbon emissions spout from the energy sector or about 350 million tons annually. The tally could be cut by about 100 million tons annually by boosting gas generation, the group says on its website.

“Our view is we should carefully review whether it makes sense at all to phase out coal very fast, replace it by gas and then you have stranded gas investments after 10 years,” RWE Chief Financial Officer Markus Krebber said in an interview with Bloomberg News in June. “The future should be renewables and storage. We’re also preparing for that.”