Rising solar: Investing in Japan’s energy transition

Introduction

The prospect of investing in Japan is undergoing a palpable renaissance amongst foreign investors. Recalling the ‘Abe bump’ of late 2012—which saw significant inflows into Japanese equities in the wake of the electoral victory of former prime minister Shinzo Abe—Japan is poised to attract sizable amounts of capital as investors respond positively to the leadership of new Prime Minister Yoshihide Suga. Investors also seem to be buoyed by the continued stewardship of Governor Haruhiko Kuroda at the Bank of Japan (BoJ). While some of the world’s largest investors take stakes in public equities and in Japanese trading houses, Japan is also attracting billions of dollars’ worth of foreign capital from leading global private equity, infrastructure, and real estate investors. The ability to invest in renewable energy assets in Japan—and thus to contribute to the country’s energy transition—also presents a significant opportunity for long-term capital from around the globe.

In fact, even amidst the Paris Agreement, and the increasing commitments by countries, companies, and communities to mitigate the impacts of climate change, Japan currently has one of the highest volumes of carbon emissions per capita. On a global basis, it is ranked fifth, behind countries such as China, the United States, and India. As a country renowned for fostering innovation, Japan has been criticized for being behind the curve in its energy policy. Coal still remains a dominant part of the country’s energy mix—a fossil fuel which contributes almost two times the level of carbon dioxide emissions than natural gas. As the world’s third largest economy, Japan relies upon foreign sources to fulfill a staggering 96 percent of its domestic energy consumption. The current combination of factors in the domestic arena in Japan—including shifting concerns around energy security; new policies designed to stimulate investment in renewable energy; mounting private sector activism in climate initiatives; and the relative undersaturation of the market—offers a potentially attractive aperture for long-term profit in alternative assets, both in renewables, as well as across the energy transition spectrum, including clean tech, grid flexibility, and storage.

Powering economic growth

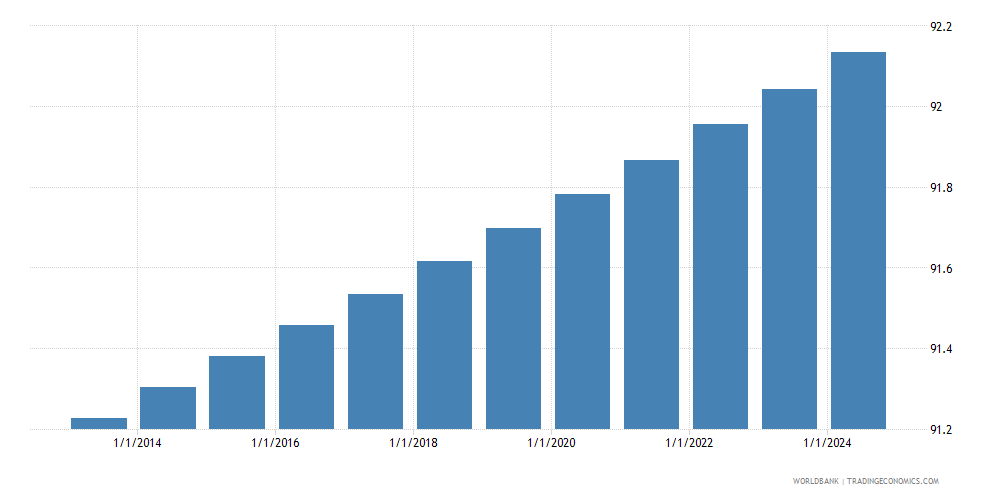

Despite being an economic powerhouse, Japan has not been geologically blessed with natural resources to fuel its manufacturing miracle, as well as its highly urbanized population. Against the backdrop of the secular shifts from old to new economy—that is, as energy-intensive industrial growth gives way to services-providing growth—the rapid pace of urbanization in Japan (Figure 1) means that the country continues to consume a high amount of electricity. Indeed, some 91.7% of Japan’s 126 million people live in an urban environment; and recognizing the implicit links between urbanization and energy consumption, Japan is the fourth largest consumer of electricity per capita on a global basis.

Figure 1: Japan—Urban population (% of total)

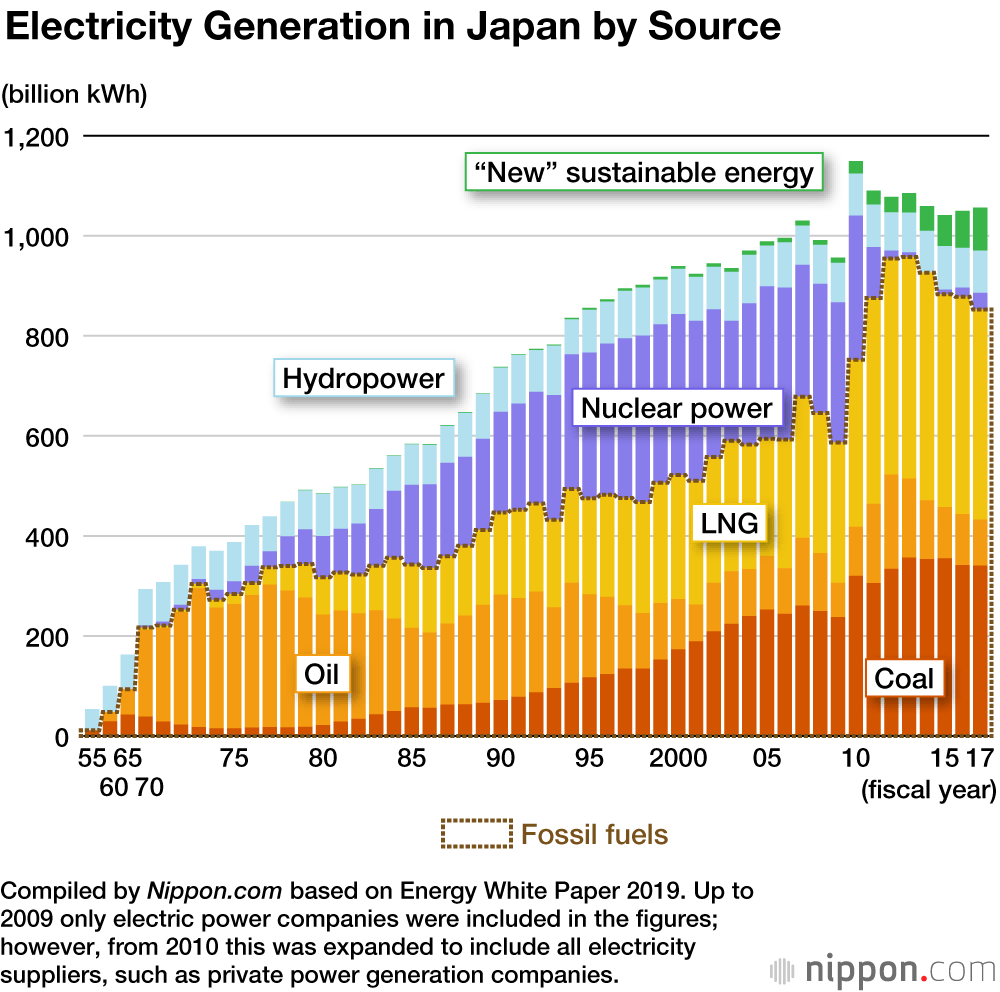

Accordingly, to fuel both industrial and urban growth, Japan has historically cemented resource ties with countries across the world—be it with oil-rich exporters in the Middle East, such as Saudi Arabia, or with natural-gas endowed countries in the Asia-Pacific region, including Australia, Indonesia, and Malaysia. After the oil shocks of the 1970s, and a corollary shock to energy security, Japanese energy policy shifted toward the increased adoption of nuclear power. Then, following the tragic Fukushima disaster in March 2011, Japan stepped up its use of coal and liquefied natural gas (LNG): as we can see in Figure 2, it effectively replaced nuclear energy with these two imported sources. In light of Fukushima, Japan has also spurred significant research and development (R&D) into other sources of energy, including hydrogen, methane hydrate (or flammable ice), tidal, or ocean energy, and ammonia as a potential ‘fuel of the future.’

Figure 2: Electricity Generation in Japan by Source

Despite these innovations and R&D activity, in the renewable realm, Japan currently uses wind and solar capacity to power only 7.6% of its total energy consumption. Indeed, as shown in Figure 3, even in light of Japan’s behemothic COVID-19 stimulus measures—amounting to some $21 billion, or 43 percent of the nation’s gross domestic product (GDP)—only about $103 million has been set aside for the energy transition. (Although Japan’s trade and industry ministry has requested an increased budget for the low-carbon transition, for the next fiscal year).

It should be noted that Japan’s topography makes producing solar and onshore wind energy rather complex: the country is comprised of some 6,850 islands, and is covered by over 70 percent mountainous region. Moreover, in recent years, there has been concern over the high cost of producing renewable energy in Japan, which has been passed on to consumers.

Figure 3: Asia’s COVID-19 stimulus and the environment

Shifting winds of energy policy

However, against the backdrop of a shifting geopolitical landscape in the Middle East—as well as heightened activism surrounding the country’s commitment to the Paris Climate accord—Japan has committed to expanding renewable energy to make up between 22 to 24 percent of its total energy mix by 2030. As part of its NDC (or Nationally Determined Contribution to the Paris Agreement), Japan has targeted to reduce emissions by 26 percent (or more) by 2030. Accordingly, the Japanese government has overhauled its existing feed-in-tariff (FiT) system, which was designed in 2012 to stimulate investment into the renewables sector. Tokyo has also recently initiated a public-private council in order to increase the capacity of offshore wind power. These new reforms are likely to boost competitiveness in a sector which has already attracted the participation of several leading European utility companies.

Notably, a recent study has shown that Japan can create 67,000 new jobs by investing in domestic renewable energy projects by 2030. This would be a positive step as countries seek to rebuild their economies in the wake of COVID-19—and potentially catalyze a movement toward investment-led growth. Indeed, while household consumption remains depressed in light of a rise in the consumption tax—as well as uncertainty from the pandemic—spurring private investment into renewables, and so an accelerated energy transition, has the potential to inject a new sense of dynamism and innovation in a sector, which is growing in demand within the domestic economy, and indeed across the globe.

From the boardroom: green vigilantism

While Japanese energy policy is shifting, a sense of strident activism on the environment springs forth from the boardrooms of financial institutions and corporations across Japan. The Japanese Climate Initiative has been signed by 159 companies, and includes many of the largest listings on the TOPIX, representing a wide array of sectors and industries. The Japanese Climate Leaders Partnership—which urges low carbon trends in business—includes signatories from some of the country’s largest banks, and even airlines. Several of these companies have urged the government to introduce carbon pricing as a way of stepping up Japan’s NDC. One of the largest Japanese corporations has vowed to triple its renewable energy usage within the next five years, to make up 15 percent of its energy mix. And in the investment space, the world’s largest pension fund continues to trumpet the need for increased awareness and reporting related to the Task Force on Climate Disclosure (TFCD), as recommended by the Financial Stability Board (FSB).

It should be noted that this sense of corporate climate activism is not limited to Japan’s domestic situation: some shareholders are calling for greater scrutiny of coal exposure and financing of Japanese projects abroad. Accordingly, Japan’s Minister of the Environment Shinjiro Koizumi announced recently that the government will place new restrictions on the financing of coal power abroad (something that the Asian Development Bank has also been encouraged to do).

Opportunities at the asset level

In a world of changing regulations, and as governments—including Japan—begin to withdraw some of the support initially provided for the energy transition, it is important to think in terms of long-term opportunities to be captured in a sector which can benefit from increasing competition.

The ability to invest in Japan’s energy transition presents an attractive destination for private capital, in both direct investments, as well as by gaining exposure via Japanese entities. For example, one Singaporean company has commenced construction on its first wind project in the Aomori prefecture in Japan. A sovereign wealth fund has increased its exposure to the solar, wind, and biomass sector in Japan by investing in a joint venture with a local player, alongside a global investment bank, while one of the largest institutional investors has invested in a mega solar farm in Japan.

And in the corporate space, some of the world’s leading infrastructure investors are in a competitive bidding process to invest in stakes in a Japanese energy and clean tech company, with a mandate to grow its business both in Japan and on a global basis. This speaks to the opportunity to deploy capital to develop projects in the growing domestic market in Japan, with an eye on long-term growth by expanding that exposure on a global and regional basis, given the formidable ties that Japanese companies and investors have forged across the Asia-Pacific region.

It should also be noted that to invest in Japan’s energy transition—and the multiplier effect of deploying that know-how and prowess abroad—is not limited to wind, solar, hydrogen, biomass, and hydro projects. Other opportunities include investing in the resilience of some of these projects, such as fortifying assets from natural disasters, including typhoons. Investing in grid improvements and smart grid technologies to enable flexibility will be critical, in addition to investing in innovations in battery storage. Some of Japan’s universities have also been important in developing R&D in these new technologies in tandem with some of the largest global companies.

Conclusion

In sum, while Japan has been the target of ire from some climate activists for its use of coal at home and abroad, and for not yet stepping up its NDC, a closer look at the history of Japanese energy policy reveals a more nuanced and complex picture. As the world’s third largest economy, its energy needs remain substantial—and the topography of Japan makes it difficult to develop solar and onshore wind capacity. Nevertheless, the relative undersaturation of the market presents a clear long-term opportunity for private investors seeking to gain exposure not only to the growing capacity of domestic projects, but also to innovations across the clean tech, grid, and storage space. Building this exposure in Japan also enables foreign investors to potentially gain access to benefit from the lucrative links which Japanese corporate, financial, investment, government, and non-governmental bodies have cemented across the Asia-Pacific region. And this opportunity is set against the backdrop of a renewed sense of dynamism and excitement in Japan under the new leadership of PM Suga—and continued stewardship of Governor Kuroda at the BoJ—a bright spot for growth in an otherwise gloomy and uncertain global economic environment.

Dr. Alexis Crow is a nonresident senior fellow with the Atlantic Council’s GeoEconomics Center and leads the Geopolitical Investing Practice for PricewaterhouseCoopers.