Solar Farms Without Subsidy Sprout From Gloomy Britain to Italy

Next to a wheat field north of London, banks of solar panels in 35 neat rows are generating electricity without any support from the government.

Despite Britain’s reputation for grey skies, the closely-held developer Anesco Ltd. is building the hybrid solar and battery facility in Milton Keynes with its own capital. It’s just one of about 15 photovoltaic projects underway from Italy to the U.K. that aren’t relying on subsidies to make a profit, according to Bloomberg NEF, which anticipates many more to come.

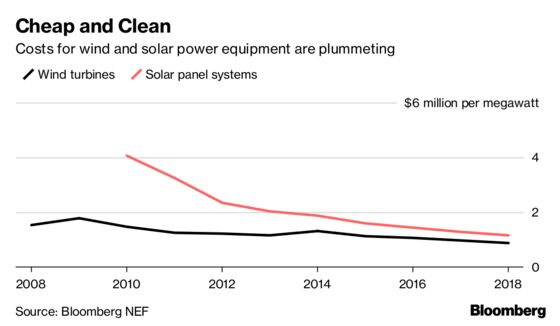

European nations are leading the way because they were among the first to back solar farms with above-market power prices and tax breaks in the early 2000s. That triggered a global manufacturing boom and 80 percent plunge in the cost of installing photovoltaics. Now, governments are cutting incentives as prices drop, and renewables are competitive with fossil fuels in more places.

“The change has come about because many governments believe that support is no longer necessary for the mature technologies which have seen significant cost reductions,” said Michelle Davies, head of clean energy and sustainability at the law firm Eversheds Sutherland LLP. “They take the view that the sector is sufficiently advanced to enable the market to find its own solutions.”

In Germany and Spain, incentives in the form of feed-in tariffs for solar electricity made it easy to anticipate how much each project would earn. That gave investors and bankers comfort enough to write loans to the industry.

Now, developers are starting to build plants that don’t rely on those mechanisms. Their costs are low enough that they can profit from selling power at the market price or by arranging a long-term power-purchase agreements, or PPAs, with big industrial consumers. Seeking a greener energy footprint, companies from AT&T Inc. to Facebook Inc. and Apple Inc. have been prominent buyers of PPAs. Those arrangements are used as security for banks lending money for construction costs.

“Corporate PPAs will be a key tool,” said Matt Setchell, head of energy at Octopus Investments Ltd., a renewables investor in London. “Clearly subsidies aren’t going to be around forever.”

In Italy, Octopus has five solar projects totaling 64 megawatts that don’t rely on support. The country’s MPS Capital Services Banca per le Imprese SpA partly funded those plants with 23 million euros ($27 million) of project finance. The developer will build more solar farms across 12 sites in Italy a total capacity of 110 megawatts.

Bankers are starting to cater for developers with PPAs. Germany’s Norddeutsche Landesbank Girozentrale recently provided 100 million euros in bridge finance to BayWa AG for photovoltiacs near Seville in Spain. Statkraft AS agreed to buy power from the plant for as long as 15 years.

“It’s not the feed in tariffs anymore that we’re banking against,” said Marco Wedemeier, a senior director at Nord/LB. “We’re banking against a PPA.”

Policy makers are taking note. Governments have been rolling back subsidies, ending some early and phasing out others. The same economics reducing the cost of solar to the point it can survive on its own also are starting to apply to other technologies.

Once the most expensive type of renewables, offshore wind farms are now being planned in Germany and the Netherlands by Orsted A/S and Vattenfall AB without any support from government. Denmark expects the trend to spread to its waters.

The subsidy-free trend will spread most quickly in the solar industry if only because those projects are smaller and quicker to build.

Other subsidy-free projects include:

- Natixis SA’s Mirova unit owns a Portuguese solar farm, financed by Banco BPI SA, PPA with Axpo Holding AG’s Iberia unit

- Iberdrola SA’s 391-megawatt Nunez de Balboa project in southwest Spain, PPA deal with Kutxabank SA

As more subsidies are abandoned, developers will tune into the wholesale power market, where prices have been rising in recent months. European benchmark rates for power have more than doubled since a trough in early 2016, reflecting higher costs for natural gas, coal and the carbon-emissions permits utilities must buy to burn fossil fuels.

“It’s an exciting development, but the big question mark is around what electricity prices will be in future,” said Pietro Radoia, analyst at Bloomberg NEF in Milan. “Either project developers lock into long-term contracts, which debt lenders value very much, or they end up being exposed to price variations, which are hard to project 10 years down the line.”

European nations are the first to get offers from developers to build solar plants without government support, partly because market structures elsewhere haven’t yet squeezed costs that low. European countries slashed incentives rapidly as the price of PV panels fell.

- In the U.S. by contrast, the federal government offers a tax credit approved by Congress to stimulate solar power.

- Latin American nations from Mexico to Brazil are using competitive auctions to reduce the cost of renewables.

- Japan and China still rely on feed-in tariffs to pay for solar power, though the Shanghai Securities News reported last month that the government has a pilot project that would give solar the same payments as coal plants receive.

Back at Anesco, revenue from the panels vary with daily fluctuations in the power market. If rates would fall too much, Chairman Steve Shine said the company could charge a bank of batteries attached to the farm instead selling at the market. Those batteries could be discharged when prices are higher.

To expand beyond Milton Keynes, Anesco is planning another four U.K. projects. It expects to raise debt from banks for the next round of projects after shouldering on its own balance sheet the 10-megawatt facility north of London.

“At the beginning we were chasing banks,” Shine said. “Now they’re chasing us. They’re starting to get their heads around it.”