Uruguay could become a hydrogen exporter by the end of the decade if it can convince private-sector investors to back efforts to use the country’s abundant renewable-energy assets to produce the green fuel, according to the state-run oil company Ancap.

The government is developing guidelines and incentives such as tax breaks for its first hydrogen fuel test project and plans to pitch it to investors as soon as this month. At least one backer will probably be selected through a competitive process this year, Alejandro Stipanicic, Ancap’s chairman, said in an interview.

So-called green hydrogen, which uses renewable electricity to split water into hydrogen and oxygen, is emerging as a potential alternative energy source to help reduce greenhouse gases. Uruguay has a glut of clean energy from wind, solar and hydropower projects, as well as a deepwater Atlantic Ocean port that would give the nation access to key export markets, Stipanicic said.

“We are going to introduce hydrogen as a source of renewable energy” for domestic use, Stipanicic said. “But the big bet is hydrogen exports.”

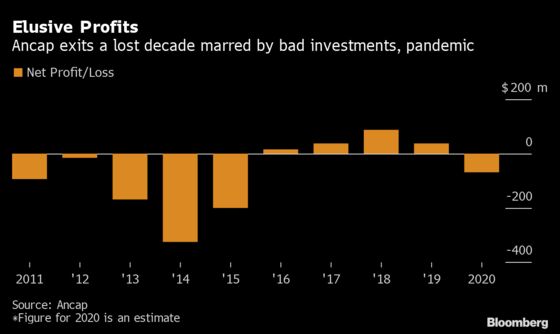

Ancap has lost money in six of the past 10 years and a limited investment budget means it will need to be “creative” to expand into the hydrogen industry, Stipanicic said. A project to export hydrogen to markets such as the European Union would likely take five to eight years to develop and could easily require an investment of at least $1 billion based on today’s technology.

The 89-year-old company, formally Administracion Nacional De Combustibles Alcohol Y Portland, already has expertise in producing hydrogen for its refinery and owns a site near the port of Montevideo that it could lease or contribute to a joint venture.

Ancap also could leverage its role as oil-industry regulator to auction offshore blocs for wind farms that could power electrolyzers that produce hydrogen and an ammonia plant. The company’s offshore oil and natural gas exploration contracts give the company an option to take minority stakes in commercially viable discoveries by third parties, and those deals could serve as a model for a hydrogen venture, Stipanicic said.

Investors poured billions into developing wind, solar and biomass power plants in the past decade. Along with hydropower, they supplied about 93% of the country’s electricity last year. Uruguay also has a significant electricity surplus, some of which it currently exports, but which could be used instead for producing hydrogen. Electrolyzing equipment costs are falling and converting hydrogen to ammonia would make it economical to transport by ship, according to a BloombergNEF report.

“The idea is for Ancap to have some sort of participation” in the hydrogen business, Stipanicic said. “But we aren’t going to lead the investment. The private sector will make the investment.”

Ancap has had preliminary talks with more than three South American companies, including refinery operators, since last March to gauge interest in business ventures such as swapping products, joint exports or the leasing of logistical infrastructure, he said.

Stipanicic is optimistic Ancap could strike a deal as soon as this year that would help it mop up unused refining and distribution capacity before the global shift away from fossil fuels makes those assets obsolete.