Storing Energy in the Freezer: Long-Duration Thermal Storage Comes of Age

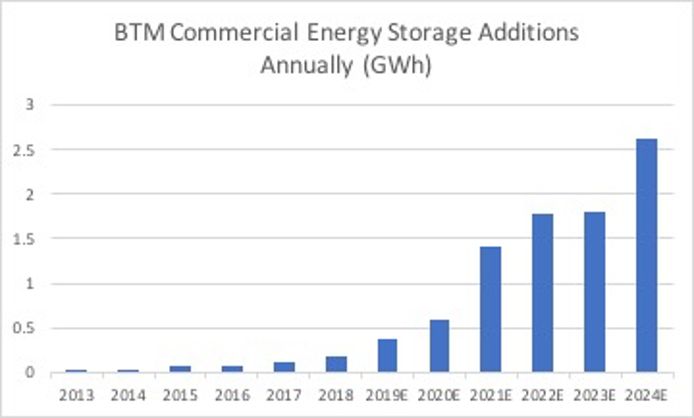

Thermal energy storage makes up a small but growing portion of the behind-the-meter energy storage market.

Jason Dreisbach fields at least half a dozen calls every week from people trying to sell him a technology to lower his energy costs. As the owner of Dreisbach Enterprises, a cold-storage facility owner with operations in Northern California, he’s a popular target. Cold storage — from frozen food warehouses to grocery and restaurant refrigeration — has one of the highest energy costs of any industry; energy expenditures are usually second only to payroll.

Dreisbach endures sales pitches that run the gamut of energy solutions, from LED lighting to rooftop solar to fuel cells. When Viking Cold Solutions reached out in 2017 with a thermal energy storage technology, his interest was piqued because, even though he had many questions, “it was not a foreign concept,” he said. The battle in cold storage is not keeping things cold, but rather removing heat. “We are constantly fighting [British thermal unit] intrusion,” Dreisbach explained. Viking Cold offered something that aided in the battle.

Cold storage facilities have long been a target for energy-efficiency and demand-response programs because of their intense energy needs. And yet, these ubiquitous facilities have not been fully tapped for their energy savings or potential as flexible energy resources. Some promising companies with mechanically complex thermal energy storage solutions targeting the commercial sectors, including the cold chain, have exited the business or turned to software-based offerings only.

It’s a tough sell to get any business, especially grocers or frozen-food warehouses, to give up valuable square footage for any energy storage solution, or to put their customers’ products in jeopardy to save on costs. Because of this, Viking Cold has found that many of its potential clients have had limited success with demand-management participation. And until recently, most utilities have not actively sought out long-duration energy storage as part of their grid flexibility portfolio. Now, that is all changing.

A big target, easily overlooked

Viking Cold Solutions didn’t set out to develop a technology for utilities to tap as a grid resource. Its founder simply wanted to move more frozen foods more efficiently between Jacksonville, Florida and Puerto Rico for clients such as Sam’s Club. The patented solution leverages thermal energy storage to the benefit of frozen-food storage providers and utilities.

In simple terms, all thermal energy solutions involve the heating or chilling of water or another medium, which is then used to shift energy loads. In the case of Viking Cold’s technology, it also improves efficiency. Thermal energy storage is currently a small but growing portion of the behind-the-meter energy storage market, according to Wood Mackenzie’s energy storage analysts.

iking Cold’s technology for frozen-food warehouses looks like a radiator that sits atop the frozen-food racking. It’s made of sealed plastic bottles filled with water and hydrated salt solutions that act as a phase-change material to absorb heat infiltration inside the freezers. There are no mechanical system components, but the phase-change material is paired with an intelligence platform that optimizes temperatures and energy use and interfaces with nearly any building or warehouse management system.

“With our technology, we essentially treat the phase-change material like a thermal battery,” said James Bell, president and CEO of Viking Cold Solutions. “We know precisely how much energy is in there. Prior to thermal energy storage, people had just guessed.” He further noted that energy-saving practices for this sector have traditionally used the food or the building as the energy-storage medium, “but now we have something specifically designed for energy storage that is safe for both food and the environment.” The systems can deliver over 12 hours of load-shifting while improving refrigeration efficiency an average of 25 percent.

Born in Florida, coming of age in California

Dreisbach Enterprises and San Diego Food Bank are two of the California-based operations that have invested in Viking Cold’s technology to run their operations more efficiently. In thermal energy storage, they have found a powerful long-duration storage solution that helps them do everything from integrating renewables more profitably to increasing resiliency during power disruptions, as well as participating in multiple utility programs in ways they couldn’t before. Viking Cold is an approved project developer in California’s Self-Generation Incentive Program, which provides funds for behind-the-meter energy storage deployments.

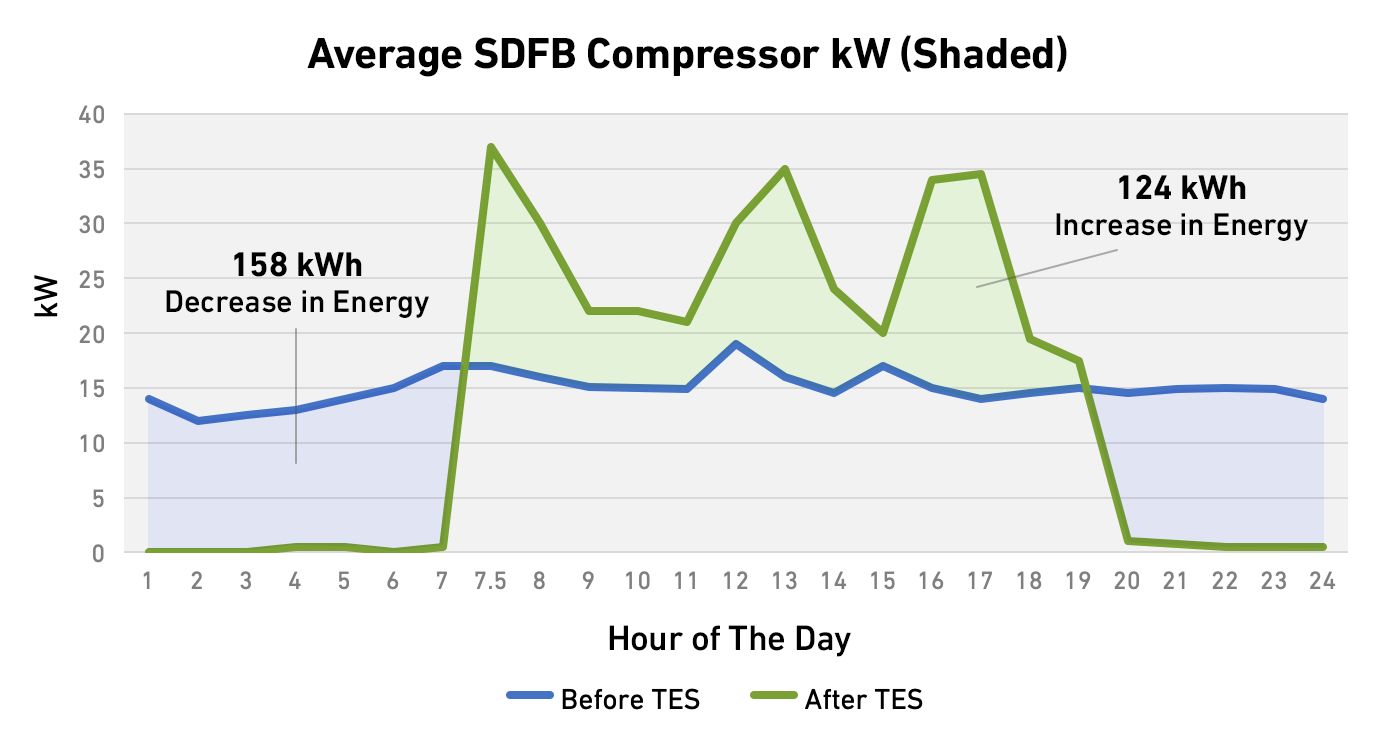

The average cold-storage warehouse has approximately 1 megawatt of energy storage potential, according to Viking Cold. In the case of Dreisbach Enterprises, in 2017 it installed the technology in a portion of one of its 100,000-square-foot Northern California facilities, which now reduces nearly half a megawatt of freezer load for 13 hours every day. Prior to the installation, Dreisbach used the conventional cold-storage industry practice known as flywheeling (also called floating), which consists of sub-cooling the food and then shutting off refrigeration systems during the expensive six-hour peak demand-charge period.

“What Viking Cold has allowed us to do is [to avoid] sub-cooling to the degree that we had, and then ride it out for much longer,” said Dreisbach. “Instead of six hours, we ride 12 or 13 hours, six days a week, without turning on our more major compressors.” The result is a 22-month payback period instead of 36. There have been other benefits: It’s simply not as uncomfortable in the warehouse when employees are working because the fans are blowing less; operations and maintenance needs and costs have been reduced, and during a recent 24-hour outage caused by a nearby Pacific Gas & Electric transformer, temperatures rose only about 5 degrees, said Dreisbach, compared to the rise of approximately 15 degrees that would have occurred without Viking Cold’s thermal energy storage (TES) technology.

San Diego Food Bank’s TES system has allowed the organization to essentially shut down compressors overnight and leverage its onsite solar array to power more of the refrigeration during the day. The facility has also reduced its morning peak, which occurs before the solar array is generating energy, by about 12 kilowatts. The overall energy savings have amounted to nearly 40 percent.

A distributed energy resource for the taking

While thermal energy storage has been available for a long time in various forms, the current juncture seems particularly well suited to the solution. Lithium-ion batteries, which dominate the energy storage market, offer about two hours of storage for utilities to tap. For heavy refrigeration loads, Viking Cold has found lithium-ion batteries are neither feasible nor economical when compared to its TES, which has a levelized cost of energy of less than $0.02 per kilowatt-hour.

At the same time, the need to incentivize load-shifting takes on new importance as intermittent wind and solar are rapidly added to the grid, and as peak mitigation increasingly becomes a focus as utilities look to displace inefficient peaker plants. Regulators are more frequently tasking utilities with providing “all-of-the-above” resource plans that include a range of distributed energy resources, energy storage in particular. Finally, utilities are looking for opportunities to be proactive with value-added services for their largest customers to prevent them from defecting.

Viking Cold’s technology can address these varying utility challenges, but it is often still viewed through an efficiency lens. That’s fine with Bell, who says the company is focused first and foremost on serving its cold-chain customers. That’s an important distinction, as some other promising thermal energy providers have prioritized chasing utility and municipal contracts rather than focusing on end-use customers. If Viking Cold can also work with energy providers, the company sees that as icing on the cake.

“A year or two ago, we had maybe one or two utilities that had incentives for us,” said Collin Coker, VP of sales and marketing at Viking Cold Solutions. “Now we have dozens.” The very nature of those incentives is also evolving. A large, investor-owned Midwestern utility is building a program that will incentivize the storage capacity of TES systems like Viking Cold’s.

“Overall, the thermal energy storage vendor ecosystem isn’t crowded today, but may see more competition as more utilities include incentives for this technology and customers realize the value proposition offered by TES,” Wood Mackenzie analysts noted in a 2019 Energy Storage Monitor report.

In the past year, Viking Cold has found that both utilities and cold-storage companies are approaching the company with their challenges, rather than simply hoping someone like Dreisbach returns the sales team’s calls. “Down the road, I see this looking like insulation did 100 years ago,” said Bell.

“Now you wouldn’t even consider a building without insulation. Going forward, why would anyone build a temperature-controlled facility without the efficiency and resiliency of TES?”