By going big on solar, the federal power agency could help attract businesses and data centers to the Southeast.

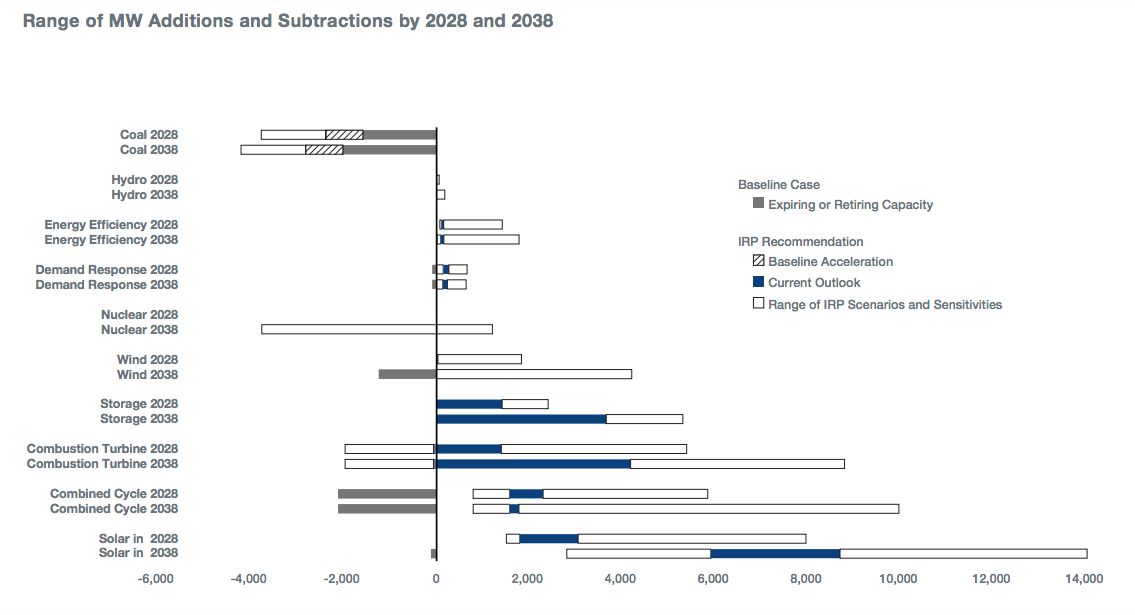

The Tennessee Valley Authority expects to add up to 14 gigawatts of solar and 5 gigawatts of energy storage over the next 20 years, a massive new clean energy addition to its current hydropower, nuclear and coal-dominant generation mix.

But TVA’s integrated resource plan (IRP) filed on Friday also calls for 2 to 17 gigawatts of natural-gas-fired generation over that time, a decision that’s drawn the opposition of the Sierra Club and other groups seeking to halt any new carbon-emitting power plants.

TVA released its draft IRP in February, and is expected to vote on the final proposal filed last week at its August board meeting in Knoxville, Tenn.

The long-range planning document doesn’t set any specific procurements in motion, and its various scenarios over the next 20 years don’t all predict the same high level of solar and storage penetration. For example, its solar estimates run from 3 gigawatts to 14 gigawatts by 2038, while its storage forecasts range from 5.3 gigawatts to nothing.

Still, TVA’s new IRP has significant implications for the 10 million or so customers in Tennessee and six other states served by the utilities that get their power from the New Deal-era federal power agency.

In simple terms, it indicates that TVA, like utilities across the country, is preparing for the shift from fossil fuels and toward carbon-free energy as a primary generation resource, while taking steps to manage the resulting grid reliability and resiliency challenges, Colin Smith, senior solar analyst with Wood Mackenzie Power & Renewables, said in a Tuesday interview.

“Solar is going to have a lot of impact in terms of dispatchability and reliability on the grid,” he said.

“They’re not the first to do this, and they’re not unique. But it outlines an important trend in what utilities can do.”

Compared to TVA’s last IRP in 2016, “this is a substantial increase in solar procurement, and even their last one was fairly aggressive for its time,” he said, in the context of where it was coming from.

As of last year, TVA’s generation mix consisted of 39 percent nuclear, 26 percent natural gas, 21 percent coal-fired, 10 percent hydro, and less than 3 percent wind and solar. That includes about 420 megawatts of utility-scale solar in operation and another 480 megawatts or so in development, Smith noted.

But the IRP calls for adding between 1,500 and 8,000 megawatts of solar by 2028. By 2038 it foresees another 3,800 to 5,500 megawatts under its base-case scenarios, or up to 14,000 megawatts “if a high level of load growth materializes.”

Growing to meet that high-end guidance would require adding about 700 megawatts a year over the next 20 years, a pace of growth that approximately matches the procurement of Duke Energy in North Carolina, Smith said.

The uncertainties involved

Whether TVA meets its high-end solar guidance will rely on many factors, and with a 20-year timeframe it’s quite possible that much of that growth will occur in the second decade, Smith noted.

Still, in the shorter term TVA has been making big solar deals with commercial and industrial offtakers — namely, big data centers — that could serve as a conduit for early-stage growth.

TVA is working with Facebook to power a data center in Alabama and with Google for data centers in Alabama and Tennessee, for example — projects that align with large-scale solar and wind procurements from data center operators across the Southeast.

“We’ve already seen this happen in TVA, and this is something that will push the solar scenario to the higher case,” Smith said. “It’s very likely they’re going to want to attract big companies to come into their territory by offering these deals.”

TVA’s IRP calls for its solar growth to come in both utility and distributed scale. But the region’s market for distributed solar has yet to take off, at least in a manner similar to the way that tech giants’ demand for clean data center electricity is driving the C&I market, Smith added.

In terms of demand, TVA expected to see significant growth over the next 20 years,

something that’s not necessarily the case in other parts of the country. At the same time, it’s expecting to lose much of its coal-fired electricity over that timeframe, as part of the nationwide trend of coal plants closing under economic and environmental pressures.

In February, TVA’s board of directors voted 5-2 to approve the 2020 closure of the Paradise coal plant in western Kentucky. The move was opposed by Republicans including President Donald Trump, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, and the state’s governor, legislature and congressional delegation.

But TVA has projected that retiring the Paradise plant, as well as another coal plant slated for retirement by 2022, the Bull Run Fossil Plant, will save customers $320 million over 10 years.

TVA’s IRP doesn’t envision adding any round-the-clock baseload resources to its resource mix to make up for those coal plant closures.

This highlights “the need for operational flexibility in the resource portfolio,” as its executive summary states, including natural gas, storage and demand response to “provide reliability and/or flexibility.”

Natural gas vs. energy storage as guarantor of grid reliability

The Sierra Club, which has worked with philanthropist and former New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg on campaigns to close coal plants and halt new natural-gas plant construction, attacked TVA’s plan for its reliance on carbon-emitting resources.

“Even as TVA is making positive strides in this new plan, its leaders must start planning for an energy future that doesn’t just trade coal for gas, which not only exposes customers to a volatile market, but also worsens the climate crisis,” Al Armendariz, deputy regional director for the Sierra Club’s Beyond Coal campaign, said in a prepared statement.

But as WoodMac’s Smith pointed out, the wide range in how much natural-gas capacity TVA expects to need over the next 20 years — from as much as 17 gigawatts, to less than 2 gigawatts — reflects the range of uncertainties the agency faces in making long-range plans to maintain grid reliability.

“As an analyst, I’m agnostic from a political standpoint,” Smith said. “But it’s worth mentioning again that the upper limit to adding renewable resources is how much resiliency and reliability you have in your system.”

Of course, natural-gas combustion and combined-cycle plants aren’t the only way to provide that reliability, he noted.

Over the coming years, the economics of energy storage — namely, lithium-ion batteries at multi-megawatt scale — as a replacement for natural-gas peaker capacity will extend from bellwether states such as California, Arizona and Texas to a broader range of U.S. markets, according to Ravi Manghani, WoodMac’s head of energy research.

TVA’s IRP calls for adding up to 2,400 megawatts of storage by 2028 and up to 5,300 megawatts by 2038 at both utility and distributed scale, although “the trajectory and timing of additions will be highly dependent on the evolution of storage technologies,” it noted.

But as Smith pointed out, recent deals in California, Arizona, Nevada and other states indicate that the price points for solar-plus-storage are dropping to compete with natural-gas-fired peaker plants in many markets. “We’re also seeing solar-plus-storage being something that’s consistently outlined in resource plans,” such as multistate Pacific Northwest utility Pacific Power’s most recent IRP.

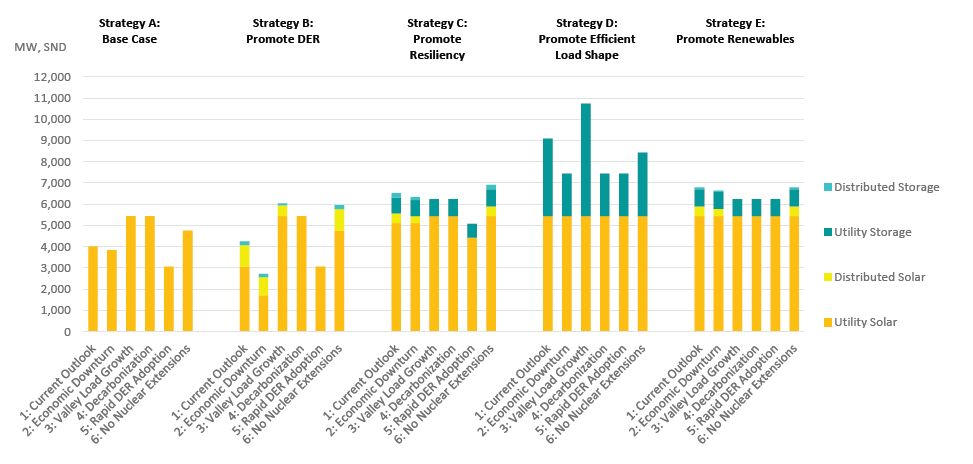

TVA’s IRP also breaks out how utility-scale and distributed solar and batteries could grow over the next 20 years, depending on whether the agency decides to adopt strategies to use these resources to promote grid resiliency, more efficient load shape, or renewable and distributed energy resources growth.

Source: greentechmedia